The Fulani, an easily identifiable people, are primarily Muslim pastoralists dotted across West Africa. They are predominantly found in Nigeria, Mali, Guinea, Senegal, and Niger. They are a nomadic cattle-herding people. This means they move about a mighty lot and leave nothing behind. This means they trek with their families, cattle and whatever else constitutes their chattel when they move from one place to the other in search of greener pastures for the herd. They settle for a while, conquer the pasture and then move on to the next convenient place. Their cattle are everything to them. Their whole lifestyle, culture and values have been shaped by their pastoralist nature. The Fulani have a rich history that dates back to the early centuries CE. Originating as nomadic herders, the Fulani expanded across West Africa, interacting with various ethnic groups and cultures. Their mobility facilitated the spread of Islam in the region, and by the 18th century, the Fulani were key players in Islamic revivalist movements. The most notable of these movements was the Fulani-led jihad of 1804-1810, which established the Sokoto Caliphate in northern Nigeria, a significant political and religious entity that lasted until the British colonization in the early 20th century.

Socio-Economic Conditions

Despite their historical significance, many Fulani communities today face socio-economic challenges. Pastoralism, their traditional way of life, has become increasingly difficult due to environmental changes, land scarcity, and competition with sedentary agricultural communities. As a result, some Fulani have migrated to urban areas or adopted sedentary farming. These transitions have sometimes led to tensions and conflicts with other ethnic groups over land and resources. Fulani communities often feel marginalised by national governments and face discrimination. In countries like Nigeria and Mali, Fulani herders have clashed with farming communities, leading to violent conflicts. These grievances are sometimes exploited by extremist groups who promise protection and socio-economic benefits in exchange for support.

The Fulani and terrorism

In recent years, the involvement of some Fulani in terrorism has garnered international attention. Groups such as Boko Haram, Al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM), and the Islamic State in West Africa Province (ISWAP) have recruited Fulani fighters, capitalising on their grievances and socio-economic vulnerabilities. Boko Haram, an extremist group based in Nigeria, has been active since the early 2000s. Initially focused on opposing Western education and promoting a strict interpretation of Islam, Boko Haram’s tactics have evolved to include violent attacks on civilians, schools, and government institutions. According to a report by the International Crisis Group (ICG), Boko Haram has recruited Fulani fighters, leveraging their knowledge of the terrain and their discontent with state authorities.

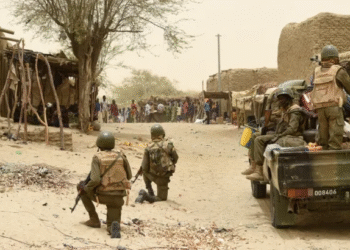

Also, Al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM) and its offshoot, Islamic State in the West African Province (ISWAP), have been active in recruiting Fulani fighters. These groups operate primarily in the Sahel region, which includes Mali, Niger, and Burkina Faso – three countries battling terrorism of all forms. Burkina Faso, for instance, has emerged as the most terrorised country in the world, according to figures from the Global Terrorism Index 2024. Compiled by the Institute for Economics and Peace (IEP), the report highlighted a 22% increase in deaths caused by terrorism, reaching 8,352, the highest number since 2017.

Interestingly, the report also noted that while the number of terrorist incidents dropped by 22% to 3,350 from 4,321, the attacks themselves have become more deadly. The number of countries experiencing at least one terrorist incident fell to 50. A significant shift in the epicentre of terrorism was observed, moving from the Middle East to the Central Sahel region of sub-Saharan Africa, which now accounts for over half of all terrorism-related deaths. For the first time in the 13-year history of the Global Terrorism Index, a country other than Afghanistan or Iraq topped the index. Nearly 2,000 people were killed in 258 terrorist incidents in Burkina Faso, representing almost a quarter of all global terrorism deaths.

The GTI 2024 reported that Burkina Faso experienced the most severe impact from terrorism, with deaths increasing by 68% despite a 17% reduction in the number of attacks. According to the Council on Foreign Relations, Jama’at Nusrat al-Islam wal Muslimeen (JNIM), Islamic State in the Greater Sahara (ISGS) and ISWAP, are very active terrorist groups in the region. The Fulani, with their extensive networks and mobility, provide valuable support to these groups. A report by the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) highlights the role of Fulani fighters in AQIM’s operations, noting that their involvement is often motivated by economic incentives and protection from rival groups.

The Fulani Herdsmen-Farmers Conflict

The conflict between Fulani herdsmen and farmers has been particularly violent in Nigeria’s Middle Belt region. According to a study by the Global Terrorism Index, this conflict has resulted in thousands of deaths and significant displacement of communities. The herdsmen-farmers conflict is not solely a religious or ethnic issue but also a struggle over land and resources exacerbated by climate change and population growth. The triggers include mistrust, xenophobia, growing land pressure, as well as pastoralists feeling they are treated as second-class citizens as far as their right to resources such as land, water and forage for their animals are concerned; theft of their livestock, and they being seen as representing elite interest since some of them are perceived as fronts for high-profile and powerful politicians or politically exposed people in the cattle business.

As a result of such conflicts, the Fulani now arm themselves while grazing their cattle. They are ever ready to shoot and kill or inflict fatal machete wounds on locals of their host communities who stand in their way. On the other hand, the local communities also do not spare the Fulani and their cattle when they trample their crops and decimate their farms. According to Climate Diplomacy, these conflicts between herders and farmers in Niger, for instance, are increasing because climate change has driven the nomadic Fulani herders of the Sahel further south, where they compete for access to land and water with settled Zarma farmers. It notes that sporadic ethnic violence has ever erupted on a local scale, which caused casualties.

The Africa Centre for Strategic Studies also points out that farmer-herder violence in West and Central Africa has increased over the past 10 years with geographic concentrations in Nigeria, central Mali, and northern Burkina Faso. It says population pressure, changes in land use and resource access, growing social inequalities, and declining trust between communities have rendered traditional dispute resolution processes less effective in some areas, contributing to the escalation of conflict.

Militant Islamist groups in central Mali, northern Burkina Faso, and parts of Nigeria, the Centre mentioned, have exploited intercommunal tensions to foster recruitment and this has had the effect of conflating farmer-herder conflict with violent extremism, significantly complicating the security landscape. The Centre also notes that violence involving the pastoralist herders in West and Central Africa—as perpetrators and victims—has been surging in recent years, adding, since 2010, there have been over 15,000 deaths linked to farmer-herder violence. Half of those have occurred since 2018, it said. The Centre notes that militant Islamist groups in central Mali and northern Burkina Faso have “instrumentalised” such divisions to inflame grievances, thereby driving recruitment. Similarly, rebel groups in the Central African Republic (CAR) have positioned themselves as defenders of pastoralist interests.

The Centre indicates that Nigeria has experienced the highest number of farmer-herder fatalities in West or Central Africa over the past decade. This trend, it observes, has been largely upward, with 2,000 deaths recorded in 2018. Violent events between pastoralist and farming communities in Nigeria have been concentrated in the northwestern, Middle Belt, and recently southern states.

Many Fulani are driven to join terrorist groups due to socio-economic marginalisation. Lack of access to education, healthcare, and economic opportunities creates a fertile ground for radicalisation. Terrorist groups exploit these vulnerabilities, offering financial incentives, social status, and a sense of belonging to disenfranchised individuals.

Political grievances also play a significant role in the radicalisation of the Fulani. Many Fulani feel excluded from political processes and decision-making at the local and national levels. This sense of exclusion can drive individuals towards extremist groups that promise to address their grievances and provide an alternative political order.

While socio-economic and political factors are significant, the role of religious ideology cannot be ignored. Extremist groups use religious narratives to justify their actions and recruit followers. For some Fulani, the promise of fighting for a purer form of Islam and against corrupt state institutions is a powerful motivator.

Analysis

For a race that is tightly bound by one religion and culture, which finds its people spread across most parts of West Africa and sees itself as marginalised and unwanted, it would be easy for its people to be roped in by any legitimate or illegitimate authority that presents them with some sense of protection, justice, restoration or retribution. They are more likely to find these in militant groups, who, themselves, exploit these sentiments for recruitment purposes. A Fulani would be more than happy to wield arms to protect his family and cattle from unfriendly hosts in a community than leave his fate and that of his cattle and family to chance. A race or people who see themselves as disrespected and looked-down-upon, always use such marginalisation as a fulcrum to rally unity among themselves since they are aware that they face a common enemy and problem. This makes it even easier for their radicalisation and fortifies their resolve to either prove a point or avenge their badly battered image and reputation. Apart from sharing one language and culture, the Fulani also practise one religion – Islam – on which fundamentalists and extremists in the Sahel, base their terrorist ideologies and philosophies. It, thus, appears the culture, religion and socio-economic circumstances of the Fulani, are easily exploitable by jihadists and terrorists. Once the Fulani are found across West Africa, they could easily be the fuel extremists need to expand their network and carry out more coordinated, concerted, transnational and West Africa-wide terrorism operations that could affect several innocent citizens in different African countries at a go. This way, the herders become the conduit for the spread of the terrorism contagion. They wouldn’t even know they were being used. They would rather be made by the terrorists to feel they were fighting for the ‘Fulani nation’. Such false consciousness would make the Fulani have a false sense of patriotism, which, unfortunately, would be the fuel for the cause of the terrorists.

Make a race or group of people feel they are fighting for a worthy cause concerning their very existence, and they will rather die fighting for that false freedom.

What can be done to avert a time bomb?

West African governments, with support from international partners, have implemented various counter-terrorism measures to address the threat posed by extremist groups. These measures include military operations, intelligence sharing, and community engagement programmes. However, the effectiveness of these efforts is often limited by corruption, lack of resources, and inadequate coordination among security agencies. Addressing the root causes of Fulani involvement in terrorism requires a comprehensive approach that goes beyond military solutions. Governments need to invest in education, healthcare, and economic development in Fulani communities. Enhancing political inclusion and addressing grievances related to land and resource conflicts are also crucial.

Community-based approaches to counter-terrorism have shown promise in some areas. Engaging local leaders, including traditional and religious authorities, can help build trust and cooperation between Fulani communities and state authorities. Programs that promote dialogue and reconciliation between herders and farmers can also reduce tensions and prevent violence.

The involvement of some Fulani in terrorism in West Africa is a complex issue rooted in historical, socio-economic, and political factors. Addressing this challenge requires a multi-faceted approach that includes not only robust counter-terrorism measures but also efforts to address the underlying causes of radicalisation. By promoting socio-economic development, political inclusion, and community engagement, West African governments and their partners can help reduce the appeal of extremist groups and build a more peaceful and stable region.

References

International Crisis Group. (2017). “Herders against Farmers: Nigeria’s Expanding Deadly Conflict.” Retrieved from https://www.crisisgroup.org/.

United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC). (2020). “The Sahel: Key Criminal and Terrorist Activities.” Retrieved from https://www.unodc.org/. Global Terrorism Index. (2020). “Measuring the Impact of Terrorism.” Retrieved from https://www.visionofhumanity.org/.