Introduction

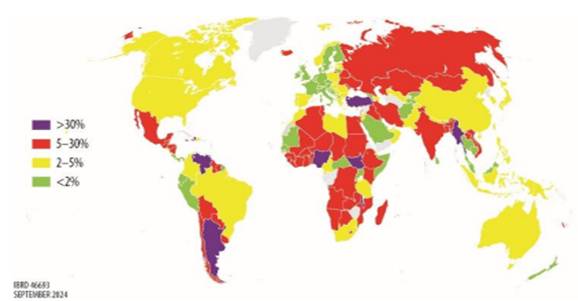

The world today is highly interconnected through various linkages, and this is expressed even through problems faced across regions. Climate change, economic instability, and geopolitical conflicts are deeply interlinked, affecting not only local but also entire regions and the global community. Of these, food insecurity is fast emerging as a critical and growing threat transcending national borders and posing a direct risk to human well-being and global stability. Traditionally viewed as a humanitarian concern, food insecurity is now recognized as a key component of national and international security. This is typified by the food inflation heatmap between May and August 2024 shown below.

Source: International Monetary Fund, Haver Analytics, Trading Economics, and World Bank Real Time Price estimates. Note: Food inflation for each country is based on the latest month from May to August 2024 for which the food component of the Consumer Price Index (CPI) and overall CPI data are available.

(https://thedocs.worldbank.org/en/doc/40ebbf38f5a6b68bfc11e5273e1405d4-0090012022/related/Food-Security-Update-CVIII-September-26-2024.pdf).

This article, focuses on how food insecurity has a new frame: a security contagion. Drawing an analogy from infectious diseases, this article indicates that, similar to the spread of infectious diseases, food insecurity poses systemic risks and is indeed interlinked. Clearly, while food shortage and crises can originate on a small scale, it can ultimately escalate to unsettle not only individual communities but also the entirety of nations and global supply chains. Framed in this light, food insecurity becomes a core security issue, not merely humanitarian in nature, and necessitates immediate action and coordination across levels of activity: local, national, and international.

Additionally, this article considers the spillover impacts of food insecurity on public health, economic stability, and geopolitical relationships. To that end, comparisons will be drawn relative to how food insecurity resembles communicable diseases in its ability to traverse national borders, with far-reaching implications. Lessons will be drawn to outline what is needed in regard to food insecurity is a more proactive and collaborative approach-one that recognizes its potentially destabilizing impacts on societies and calls for resilient, sustainable global food systems that can meet this challenge. The paper will also identify strategies of containment and prevention that give insight into how the global community might take steps to mitigate the risks associated with food insecurity before it reaches a more critical point.

Defining food (in)security

The effort to eradicate hunger, food insecurity, and other forms of malnutrition has been the topic of many studies (Xie et al., 2021). Despite years of significant progress, most countries, especially in developing countries such as Sub-Saharan Africa, still grapple with severe food insecurity challenges (Beyene, 2023; Cheteni, Khamfula, & Mah, 2020). It was not until the mid-1970s, with the new food insecurity concerns, that world leaders would recognize for the first time their collective responsibility to eliminate hunger and malnutrition (Peng & Berry, 2019). However, in the 48 least developed countries, per capita food consumption decreased between 1980 and 1998, while in most of the developing world, it has been increasing (Vasileska & Rechkoska, 2012). The 1996 World Food Summit (WFS) had predicted that the number of hungry people in the world would fall by at least 20 million each year between 2000 and 2015. Whereas in some areas great steps forward were taken in the twenty years up to the year 2000, the latest data on the number of undernourished people around the world demonstrate that since the 1996 WFS, there has been an average annual reduction of just 2.5 million, which is well below the level required to achieve the WFS goal of reducing by a significant margin the prevalence of undernourishment by 2015 (Gentilini & Webb, 2008; Wudil et al., 2021). In the last three decades, the increase in food production has been faster than population increase in the world. However, in 2018–2019, there were over 830 million people suffering from physical food insecurity in the world, mainly in South Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa; it does not count those suffering from obesity or micronutrient deficiency, affecting more than one billion persons (Wudil et al., 2021).

To define food insecurity, one must first understand what food security is, as both are dynamic, reciprocal, and time dependent, and the outcome depends on how the stresses of food insecurity interact with coping mechanisms (Peng & Berry, 2019). According to the Food and Agriculture Organization’s (FAO) 2001 annual report on food security, the current, generally recognised definition of food security is the state in which all people, at all times, have physical, social, and economic access to enough safe, nourishing food that satisfies their dietary needs and food preferences for an active and healthy life (FAO, 2002).It has been expanded to encompass the availability, accessibility, and consumption of enough nutrient-dense food to satisfy a population’s nutritional demands (Peng & Berry, 2019). According to varying levels, four aspects of food security have been identified:

1) Food availability on a national scale.

2) Food accessibility inside the household.

3) Food utilisation on an individual basis.

4) Food production stability, which might be viewed as a temporal component influencing all levels.

For food security to exist, all four of these aspects must remain intact. The significance of sustainability, which may be viewed as the long-term aspect of food security, has been emphasised by more recent advances. Any of the following points on the food security pathway—availability, accessibility, utilisation, and stability—can experience the stresses of food insecurity. The coping reactions that are evoked can occur at the individual, household, or national levels. According to Peng and Berry (2018), stress causes coping responses that may or may not be sufficient, necessitating adjustments to coping mechanisms until food security is restored. These two processes are linearly connected with reiterative feedback loops.

The conceptual definition of food insecurity after establishing the dialectical link between it and food security requires discussion. The ongoing concern about always having access to enough food at a reasonable price is known as food insecurity (Paslakis et al., 2021). It will happen if there are issues with the food production-consumption chain at any one level. Food insecurity, as it is practically measured in the United States, is defined as the need to obtain food through socially unacceptable means, insufficiency in the quantity and type of food needed for a healthy lifestyle, or uncertainty about future food availability and access (National Research Council, 2006). Food insecurity can occur when food is available and accessible but cannot be used due to physical or other limitations, such as the old or reduced physical functioning, in addition to the most prevalent constraint, which is a lack of financial means (ibid).

The Contagious Nature of Food Insecurity

Food insecurity is not confined to the people directly affected by it; it has a ripple effect that can destabilize entire societies and even whole nations. This contagion begins with scarcity, an economic condition that occurs when demand exceeds supply (Sun & Teichert, 2022). When food systems break down—whether due to economic crises, climate change, political instability, or pandemics—communities face shortages, price hikes, and lack of access to nutrition (Fanzo et al., 2021; Muna, 2024). The impact quickly transcends national borders due to the interconnectedness of global trade, climate patterns, and geopolitical dynamics. Like the spread of a disease, food crisis in one region can quickly affect neighboring regions, triggering migration, political unrest, and economic downturns.

In the 2007-2008 global food crisis, when rising food prices and crop failures—due in part to climate events like droughts—led to widespread hunger in the Global South, there were ripple effects felt in both developed and developing nations (McMichael, 2009). Similarly, ongoing conflicts in areas like Yemen, Syria, and the Horn of Africa have caused food shortages that not only affect those directly involved but destabilize neighboring countries, putting pressure on international humanitarian efforts. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has caused the greatest military-related increase in global food insecurity in at least a century. Although the issue has receded from headlines, impacts persist: the UN Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) predicts that millions will still be chronically undernourished in 2030 because of Russia’s war (Welsh, 2024). In addition, COVID-19 affected the world’s socioeconomic and food security more than other infectious diseases (Kakaei et al., 2022; Kawakatsu et al., 2024)

The Domino Effect: Security, Health, and Socioeconomic Impact

Food insecurity has massive ramifications beyond direct physical lack of food. Much as an infectious disease spreads through populations, food insecurity turns into a landslide of interlaced problems: poor nutrition promotes public health disasters, malnutrition, stunted growth in children, and weakened immune systems that easily make populations suffer from diseases (Morales et al., 2023). Foodborne diseases or a lack of proper nutrition make people ill, further overstretching already fragile health systems.

But the effects do not stop at public health. Food insecurity also has a strong impact on economies: hungry people are less productive, and overall economic output for entire communities may be lowered, holding back development. The education sector is often one of the first institutions to feel the pressure, as children unable to access sufficient food struggle to learn, further perpetuating the cycle of poverty as well as inequality (Siddiqui et al., 2020). These disruptions have the potential to snowball, affecting long-term societal stability, much like the aftereffects of a pandemic that leave communities grappling with the scars of its spread.

Food Insecurity and National Security: A Geopolitical Threat

Food insecurity transcends borders, turning it into a security problem with massive geopolitical implications. A country relying heavily on food imports or experiencing the destruction of domestic agricultural systems becomes susceptible to internal instability, as well as to pressure from external factors. Scarcity of resources might result in rivalry over arable land, water, and energy resources, making tensions between countries even worse.

The link between food insecurity and conflict speaks for itself. An example is Syria, where lengthy droughts, coupled with inadequate agricultural policies, gave rise to a food shortage that was, among other political reasons, instrumental in the outbreak of the civil war in 2011 (Selby, Dahi, Fröhlich, & Hulme, 2017). Similarly, food insecurity in sub-Saharan Africa, particularly Sahel, has sparked migration crises and helped to nurture the emergence of such terrorist forces that can only prosper upon the sufferings of people.

International cooperation will dampen these risks. Countries with resilient food systems and excess resources have a role to play in supporting countries in crisis, not only out of humanitarian concern but as part of a broader strategy to maintain regional and global stability.

The Global Response: Treating Food Insecurity Like a Pandemic

One of the most effective ways to address food insecurity as a security contagion is to treat it with the same urgency and cooperation that the world has shown in responding to global health crises. Just as governments and international organizations mobilized to control the spread of COVID-19, a similar collective response is required to prevent and contain food insecurity on a global scale. Early detection and prevention are crucial. Identifying at-risk populations and addressing the root causes of food insecurity—such as poverty, inequality, and climate change—should be priorities for governments and international organizations. Investments in sustainable agriculture, resilient food systems, and climate adaptation are necessary to prevent the destabilizing effects of food insecurity.

What it requires is to strengthen international networks of aid in such a manner that it results in emergency food assistance to people in need of faster and more proficiency. But more fundamentally, there is also a need for the long-term development programs; for instance, increasing food security, providing stimulus to local agriculture, investment in infrastructure, along with social nets. These works of mitigation not only reduce food insecurities but take control of and minimize the further social and economic vulnerabilities that would foster them. Much like the way in which the spread of an infectious disease is prevented, building resilience in vulnerability to food insecurity includes both short-term containment and longer-term structural changes. Containment may involve the mobilization of international humanitarian aid, strengthening supply chains, and expansion of trade agreements in a way that makes food resources flow to where they are needed most.

Long-term resilience, however, involves rethinking our global food systems. In many ways, food insecurity is a reflection of deep-rooted inequalities and unsustainable practices. In a world where millions of tons of food are wasted annually, better distribution mechanisms and sustainable farming techniques could help prevent the spread of food insecurity. In addition, policies that address climate change, protect biodiversity, and reduce environmental degradation are critical to ensuring that food systems can withstand future shocks.

Conclusion

Framing food insecurity as a security contagion emphasizes its urgency and the interconnectedness of the world’s challenges. Just as the spread of a contagious disease threatens global health, the spread of food insecurity can destabilize economies, societies, and entire regions. Addressing food insecurity requires a collective global response, involving prevention, containment, and the creation of resilient food systems. If we treat food insecurity as a security issue, we can take the necessary steps to prevent it from becoming a global crisis—before it spreads any further.

Reference

Beyene, S. D. (2023). The impact of food insecurity on health outcomes: Empirical evidence from sub-Saharan African countries. BMC Public Health, 23(1). Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-023-15244-3

Cheteni, P., Khamfula, Y., & Mah, G. (2020). Exploring food security and household dietary diversity in the Eastern Cape Province, South Africa. Sustainability, 12(5), 1851.

Council, N. R., & Council, N. R. (2006). Food insecurity and hunger in the United States: An assessment of the measure. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. doi, 10, 11578.

Fanzo, J., Bellows, A. L., Spiker, M. L., Thorne-Lyman, A. L., & Bloem, M. W. (2021). The importance of food systems and the environment for nutrition. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 113(1), 7-16. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/nqaa313

FAO (2002) The State of Food Insecurity in the World 2001. Food and Agricultural Organization, Rome.

Gentilini, U., & Webb, P. (2008). How are we doing on poverty and hunger reduction? A new measure of country performance. Food Policy, 33(6), 521-532.

Kakaei, H., Nourmoradi, H., Bakhtiyari, S., Jalilian, M., & Mirzaei, A. (2022). Effect of COVID-19 on food security, hunger, and food crisis. COVID-19 and the Sustainable Development Goals, 3-29. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1016/b978-0-323-91307-2.00005-5

Kawakatsu, Y., Damptey, O., Sitor, J., Situma, R., Aballo, J., Shetye, M., & Aiga, H. (2024). Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on food availability and affordability: An interrupted time series analysis in Ghana. BMC Public Health, 24(1). Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-024-18745-x

McMichael, P. (2009). Interpreting the World Food Crisis of 2007-08. Review (Fernand Braudel Center), 32(1), 1–8. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/40647786

Morales, F., Montserrat-de la Paz, S., Leon, M. J., & Rivero-Pino, F. (2023). Effects of Malnutrition on the Immune System and Infection and the Role of Nutritional Strategies Regarding Improvements in Children’s Health Status: A Literature Review. Nutrients, 16(1), 1. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16010001

Muna, A. F. (2024). The Global Food Crisis: How Geopolitical Conflicts and Climate Change are Disrupting Food Security. BIPSS Commentary, 1-19.

Paslakis, G., Dimitropoulos, G., & Katzman, D. K. (2021). A call to action to address COVID-19–induced global food insecurity to prevent hunger, malnutrition, and eating pathology. Nutrition reviews, 79(1), 114-116.

Peng, W., & Berry, E. M. (2018). Global nutrition 1990–2015: a shrinking hungry, and expanding fat world. PloS one, 13(3), e0194821.

Peng, W., & Berry, E. M. (2019). The Concept of Food Security. Encyclopedia of Food Security and Sustainability, 1-7. https://doi.org/10.1016/b978-0-08-100596-5.22314-7

Selby, J., Dahi, O. S., Fröhlich, C., & Hulme, M. (2017). Climate change and the Syrian civil war revisited. Political Geography, 60, 232-244. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polgeo.2017.05.007

Siddiqui, F., Salam, R. A., Lassi, Z. S., & Das, J. K. (2020). The Intertwined Relationship Between Malnutrition and Poverty. Frontiers in public health, 8, 453. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2020.00453

Sun, H., & Teichert, T. (2022). Scarcity in today’s consumer markets: Scoping the research landscape by author keywords. Management Review Quarterly, 74(1), 93-120. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11301-022-00295-4

Vasileska, A., & Rechkoska, G. (2012). Global and regional food consumption patterns and trends. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 44, 363-369.

Welsh, C. (2024). Russia, Ukraine, and Global Food Security: A Two-Year Assessment. Retrieved January 20, 2025, from https://www.csis.org/analysis/russia-ukraine-and-global-food-security-two-year-assessment

Wudil, A. H., Usman, M., Rosak-Szyrocka, J., Pilař, L., & Boye, M. (2022). Reversing Years for Global Food Security: A Review of the Food Security Situation in Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA). International journal of environmental research and public health, 19(22), 14836. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192214836

Xie, H., Wen, Y., Choi, Y., & Zhang, X. (2021). Global trends on food security research: A bibliometric analysis. Land, 10(2), 119.