Introduction

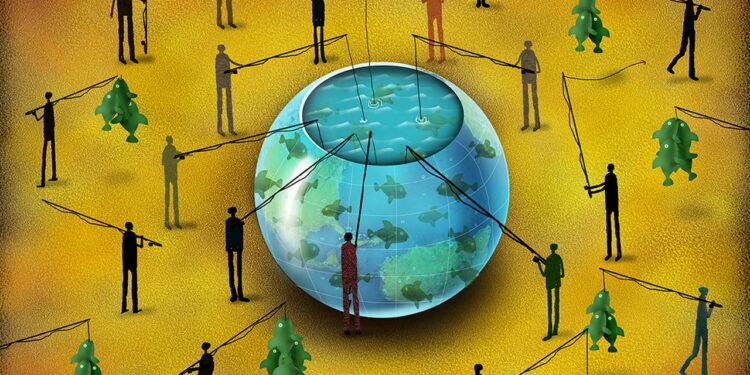

In many African countries, including Ghana, natural resources such as forests, water bodies, agricultural land as well as fisheries are important to the livelihoods of millions of people (Adom, Reid, Afuye & Simatele, 2024; Baafi, 2024). However, the management of these resources has become increasingly challenging as the demands on them grow due to population growth, urbanisation, and economic pressures (see Agyare, Holbech, & Arcilla, 2024; Puplampu & Boafo, 2021; Takyi et al., 2021). The concept of “the tragedy of the commons,” conceptualised in 1833 by British writer William Forster Lloyd but popularised by American ecologist and philosopher Garrett Hardin in 1968, offers a framework for understanding how individuals, acting in their own self-interest, can inadvertently deplete shared resources, resulting in long-term collective harm.

Hardin’s theory suggests that when resources are held in common or shared by a group of individuals without clear ownership, there is a possibility for each individual to over use the resource in question resulting in its depletion. This analytical framework remains highly important to the resource management challenges faced by Ghana today, where issues such as overfishing, deforestation, and illegal mining (locally known as Galamsey) have reached critical levels. This article revisits Hardin’s tragedy of the commons theory and applies it to Ghana’s current resource management struggles, while offering potential solutions.

Understanding the Tragedy of the Commons in the Ghanaian Context

Garret Hardin (1915- 2003) was a well known biologist especially for his works on evolution and natural selection (Frischmann, Marciano, & Ramello, 2019). In both his academic and nonacademic works, Hardin emphasised the need to control population. In his 1968 article, which Hardin wrote chiefly to warn of the dangers of overpopulation, he famously applied the term “commons” to a great variety of scenarios in which some resource is open to all, with few constraints on resource use. Hardin’s central argument in the Tragedy of the Commons is that when resources are shared by a group, members of the group acting out of self-interest will often overuse or deplete these resources, leading to environmental degradation. He used William Forster Lloyd’s example of a pasture shared by multiple herders, where each herder seeks to maximise their own benefit by adding more livestock. While each herder gains a small profit from their additional animals, the cumulative effect of all herders adding more animals results in the degradation of the pasture, which harms everyone in the long run. In the scenario, he argued, the tendency of each individual is to use the resource to maximise his own immediate interest while neglecting investment or effort that might conserve the resource for others or for future common use.

According to Hardin’s thesis, each individual rationally calculates that he can take all the gain from his own use of the common resource while sharing the losses with all the other users. The tragedy happens because, by the same reasoning, all of the users collectively exhaust the common good. Hardin uses Thomas Hobbes’ description of the state of nature to explain a similar phenomenon in the situation of the commons. It is Hobbes’ contention that in the absence of a central power to impose laws and order, people in the state of nature would behave on the basis of self-preservation, guided by their own desires and there would be perpetual war and insecurity (Navari, 1996; Read, 1991; Sadler, 2010). In the same manner, in the example of the commons, in the absence of a governing body to control use, people will pursue their own self-interest and over use the resource, causing depletion or devastation of the commons. Hardin applies Hobbes’ logic by asserting that the absence of a governing body to control access to communal resources results in what he referred to as the “tragedy“, the overuse of resources. Just as Hobbes believed that life without a sovereign authority would be “nasty, brutish, and short,” Hardin suggests that life without regulation of shared resources leads to a tragic and unsustainable future for everyone.

In the Ghanaian context, common-pool resources are vital to both the economy and the well-being of the population. These include forests, water resources, grazing land, and fisheries, all of which are used by local communities for sustenance and income. Traditionally, Ghanaian communities practiced a form of resource-sharing based on indigenous knowledge and collective management systems (Asante et al., 2017; Baaweh et al., 2022; Yahaya, 2012). For instance, in rural areas, community forests and farmland were often governed by local chiefs or elders who maintained rules about when and how to harvest resources, ensuring sustainability for future generations (see Adjei-Cudjoe, 2022). However, the rapid increase in population, alongside the development of the economy and technology, has strained these systems (Obiero et al, 2023; Tom, Sumida Huaman, & McCarty, 2019). Resources such as land, forests and water are increasingly seen as public goods freely accessible by anyone, leading to overuse. Hardin’s theory comes into play in the case of Ghana’s Galamsey (illegal mining), where individuals, driven by the promise of quick financial gains, engage in environmentally destructive practices without regard for the long-term impacts on the environment or the community as a whole. This form of behavior mirrors the core concept of Hardin’s tragedy, where individual actions, though rational in the short term, lead to long-term collective harm.

Factors Contributing to the Tragedy of the Commons in Ghana

To begin, population growth and increased demand is one of the main factors contributing to the tragedy of the commons in Ghana. This was the main worry of Hardin and Thomas Malthus when he argued that a finite world can only support a finite population. Although they were heavily criticised, their argument about the population problem remains relevant today especially in Africa and the Global South where urban population is projected to double by 2050. Specifically, Ghana’s population is growing rapidly, which puts increasing pressure on land, water, and other common-pool resources. The growing demand for land and access to water has led to the overexploitation of these resources, particularly in rural areas. Furthermore, as more people migrate to urban centers, there is greater demand for resources like timber as well as fuelwood, which further deplete the nation’s natural resources.

Secondly, in most regions, the lack of proper governance and enforcement systems leads to the tragedy of the commons. The government’s failure to enforce regulations concerning deforestation, fishing, or illegal mining gives people the liberty to abuse resources without any fear of punishment. This is especially true in the mining industry, where despite the government attempting to stop them, Galamsey activities go on unabated.

Thirdly, most Ghanaians, particularly those in rural areas, depend on natural resources for a living. For small-scale farmers, fishermen and miners, resource utilization is frequently spurred by the immediate desire for income, in certain cases prompting them to exploit resources in unsustainable manners. Additionally, collective ownership of resources by a large group of people can sometimes result in the “free-rider” dilemma, where members over-utilize their portion without playing a role in the conservation of the resource.

Modern-Day Impacts of the Tragedy of the Commons in Ghana

Deforestation, soil erosion, water pollution, and the loss of biodiversity are some of the most visible effects of the tragedy of the commons in Ghana. For instance, galamsey activities in the Ashanti Region, Eastern and Western Regions of Ghana has led to massive loss of forest cover resulting in loss of aquatic and terrestrial habitats affecting the distribution of flora and fauna ultimately distorting the ecological structures of local communities (Ofori et al., 2024) . In freshwater aquatic environments, the Pra, Ankobra, Oti, Offin and Birim rivers have all been contaminated, transforming them into various shades of brown (Bedu-Addo, Okofo, Ntiamoah, & Mensah, 2024; Bessah et al., 2021; Kuffour et al., 2020; Boateng et al., 2014).

Resource depletion has caused social as well as economic instability. As fishing communities face declining catches and farmers see reduced yields due to soil degradation, local economies suffer. Poverty is exacerbated, and rural communities become increasingly vulnerable. The conflict over access to resources, such as land and water, often leads to tensions between individuals, communities, and sometimes even government agencies.

Water supply contamination and exposure to harmful chemicals, particularly in mining towns, is very hazardous to health. Mercury, for example, a heavy metal used to combine gold particles, is one very insidious problem. When released into bodies of water, it is transformed into methylmercury, a very toxic form that accumulates in fish and other aquatic organisms. Human intake of polluted fish can lead to mercury poisoning, which occurs in the form of neurological and developmental issues in human beings, particularly in children (Mensah & Tuokuu, 2023; Mensh & Darku, 2021).

Managing the Commons: Solutions and Alternatives

Hardin’s proposed solutions to the tragedy of the commons are privatisation and state control, while effective in some contexts, may not be suitable for Ghana. This observation is particularly applicable in examining the pivotal role of local government and community ownership in resource management (Adjei-Cudjoe, 2022). Lessons from Ghana’s experience with Structural Adjustment Policies (SAPs) indicate that efforts at privatising common resources widened inequalities instead of addressing the underlying problems (see Terry, 2019). Via the SAPs which were forced upon developing countries by international financial institutions like the IMF and World Bank, privatisation resulted in the loss of local control over resources which were managed by communal systems. The move towards privatisation brought about increased inequalities, whereby the rich individuals or firms gained control over resources, and the local people were excluded.

This process was especially evident in land and water, where the traditional communal control and ownership were undermined, leading to incidences of land grabbing and exploitation of local resources (see the example of Ada salt mining; Adina and surrounding communities). State control, on the other hand, presents a different set of issues. Although it can avert the tragedy of the commons by way of regulation, the success of state management in Ghana has frequently been undermined by political instability, capacity shortage as well as corruption (Asante, 2023; Asomah, 2019; Hackman et al., 2021). Furthermore, centralisation of control can marginalise local communities, overlooking their extensive knowledge and practices that are paramount to effective resource management (Adeyanju et al., 2021).

Elinor Ostrom, a Nobel Prize-winning political economist, developed important insights into how common-pool resources are governed that directly contradict the findings of Hardin’s Tragedy of the Commons. While Hardin argued that common-pool resources would inevitably suffer from over-exploitation without privatisation or strong government control, Ostrom (1990) presented a more optimistic and nuanced view. Her work emphasised that local communities are often capable of effectively managing shared resources through collective action. Ostrom criticised simple, top-down solutions to the problem of commons management, such as privatisation or state control, arguing that these do not account for the complexity of local contexts. She stressed that while formal legal frameworks can support common governance, informal rules, norms, and local practices are often just as important for effective management. Her findings showed that people are, in fact, capable of developing sustainable management systems on their own so long as they are given the tools, support, and freedom they need.

Based on these insights, solutions to Ghana’s tragedy should better aim at building upon those communal systems rather. Locally centered empowerment strategies, involving people in decision-making processes, and drawing upon traditional knowledge systems can yield more equitable and sustainable means of managing resources. Policies also need to address the root causes of inequality in such a way that every group has access to resources on an equal level and local communities retain authority over the resources they depend upon.

Conclusion

The tragedy of the commons remains a relevant framework for describing Ghana’s resource management challenges today. Reckless resource use such as forests, water, and fisheries threatens the environment and livelihoods of millions of people. Elinor Ostrom’s work has profoundly influenced how scholars, policymakers, and practitioners conceptualize managing common-pool resources. By emphasizing the value of local knowledge, participation, cooperation, and adaptive governance, Ostrom provided a complete and contrasting solution to Hardin’s Tragedy of the Commons pessimistic prediction. Her recommendations are highly relevant even today for resource management in nations like Ghana, where local communities face increasing pressures on common resources but also possess long-established institutions of collective action as well as knowledge. By applying Ostrom’s rules, Ghana will be able to overcome the outdated dichotomy of privatisation and state control as prescribed by Hardin and embrace cooperative, decentralised as well as adaptive forms of governance that blend the community traditions and modern environmental concerns.

Reference

Adeyanju, S., O’Connor, A., Addoah, T., Bayala, E., Djoudi, H., Moombe, K., Reed, J., Ros-Tonen, M., Siangulube, F., Sikanwe, A., & Sunderland, T. (2021). Learning from Community-Based Natural Resource Management (CBNRM) in Ghana and Zambia: Lessons for integrated landscape approaches. International Forestry Review, 23(3), 273-297. https://doi.org/10.1505/146554821833992776

Adjei-Cudjoe, B (2022). The Potentials, Risks, and Insights gained from Indigenous Planning on Degrowth in Ghana. Master thesis, University of Groningen.

Adom, R. K., Reid, M., Afuye, G. A., & Simatele, M. D. (2024). Assessing the Implications of Deforestation and Climate Change on Rural Livelihood in Ghana: A Multidimensional Analysis and Solution-Based Approach. Environmental Management, 74(6), 1124-1144. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00267-024-02053-6

Agyare, A. K., Holbech, L. H., & Arcilla, N. (2024). Great expectations, not-so-great performance: Participant views of community-based natural resource management in Ghana, West Africa. Current Research in Environmental Sustainability, 7, 100251. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.crsust.2024.100251

Asante, E. A., Ababio, S., & Boadu, K. B. (2017). The Use of Indigenous Cultural Practices by the Ashantis for the Conservation of Forests in Ghana. SAGE Open, 7(1). https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244016687611 (Original work published 2017)

Asante, K. T. (2023). The politics of policy failure in Ghana: The case of oil palm. World Development Perspectives, 31, 100509. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wdp.2023.100509

Asomah, J. Y. (2019). What Are the Key Drivers of Persistent Ghanaian Political Corruption? Journal of Asian and African Studies, 54(5), 638-655. https://doi.org/10.1177/002190961982633

Baafi, J. A. (2024). Unraveling Ghana’s Resource Curse Hypothesis: Analyzing Natural Resources and Economic Growth with a Focus on Oil Exploration. Economies, 12(4), 79. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies12040079

Baaweh, L., Baddianaah, I., & Baatuuwie, B. N. (2022). Traditional Knowledge and Practices in Natural Resource Conservation: A Study of the Zukpiri Community Resource Management Area, Ghana. International Journal of Rural Management, 19(2), 253-273.

https://doi.org/10.1177/09730052221087020 (Original work published 2023)

Bedu-Addo, K., Okofo, L. B., Ntiamoah, A., & Mensah, H. (2024). Pollution of water bodies and related impacts on aquatic ecosystems and ecosystem services: The case of Ghana. Heliyon, 10(24). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e40880

Bessah, E., Raji, A. O., Taiwo, O. J., Agodzo, S. K., Ololade, O. O., Strapasson, A., & Donkor, E. (2021). Gender-based variations in the perception of climate change impact, vulnerability and adaptation strategies in the Pra River Basin of Ghana. International Journal of Climate Change Strategies and Management, 13(4/5), 435–462. https://www.emerald.com/insight/content/doi/10.1108/IJCCSM-02-2020-

Boateng, D. O., Nana, F., Codjoe, Y., & Ofori, J. (2014). Impact of illegal small scale mining

(Galamsey) on cocoa production in Atiwa district of Ghana. Int J Adv Agric Res, 2, 89–

99. https://www.academia.edu/download/77743706/Boateng_et_al.pdf

Frischmann, B. M., Marciano, A., & Ramello, G. B. (2019). Retrospectives: Tragedy of the Commons after 50 Years. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 33(4), 211-228. https://doi.org/10.1257/jep.33.4.211

Hardin, G. (1968). The Tragedy of the Commons. Science, 162, 1243-1248.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1126/science.162.3859.1243

Hackman, J. K., Ayarkwa, J., Osei-Asibey, D., Acheampong, A., & Nkrumah, P. A. (2021). Bureaucratic Factors Impeding the Delivery of Infrastructure at the Metropolitan Municipal and District Assemblies (MMDAs) in Ghana. World Journal of Engineering and Technology, 9(3), 482-502. https://doi.org/10.4236/wjet.2021.93032

Kuffour, R. A., Tiimub, B. B. M., Manu, I., & Owusu, W. (2020). The effect of illegal mining

activities on vegetation: A case study of Bontefufuo Area in the Amansie West District

of Ghana. East African Scholars Journal of Agriculture and Life Sciences, 3(11).

https://doi.org/10.36349/easjals.2020.v03i11.002

Mensah, A. K., & Tuokuu, F. X. D. (2023). Polluting our rivers in search of gold: How

sustainable are reforms to stop informal miners from returning to mining sites in

Ghana? Frontiers in Environmental Science, 11, 583. https://doi.org/10.3389/fenvs.2023.1154091

Mensah, E. O., & Darku, E. D. (2021). The impact of illegal mining on public health: A case

study in kenyasi, the ahafo region in Ghana. Technium Soc. Sci. J., 23, 1.

https://techniumscience.com/index.php/socialsciences/article/view/4503

Navari, C. (1996). Hobbes, the State of Nature and the Laws of Nature. In: Clark, I., Neumann, I.B. (eds) Classical Theories of International Relations. St Antony’s Series. Palgrave Macmillan, London. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-349-24779-0_2

Obiero, K. O., Klemet-N’Guessan, S., Migeni, A. Z., & Achieng, A. O. (2023). Bridging Indigenous and non-Indigenous knowledge systems and practices for sustainable management of aquatic resources from East to West Africa. Journal of Great Lakes Research, 49. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jglr.2022.12.001

Ofori, S. A., Dwomoh, J., Yeboah, E. O., Martin, A. L., Nti, S., Philip, A., & Asante, C. (2024). An ecological study of galamsey activities in Ghana and their physiological toxicity. Asian Journal of Toxicology, Environmental, and Occupational Health, 2(1), 53-72. https://doi.org/10.61511/ajteoh.v2i1.2024.395

Ostrom, E. (1990). Governing the Commons: The Evolution of Institutions for Collective Action. Cambridge University Press.

Puplampu, D. A., & Boafo, Y. A. (2021). Exploring the impacts of urban expansion on green spaces availability and delivery of ecosystem services in the Accra metropolis. Environmental Challenges, 5, 100283. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envc.2021.100283

Read, J. H. (1991). Thomas Hobbes: Power in the State of Nature, Power in Civil Society. Polity, 23(4), 505–525. https://doi.org/10.2307/3235060

Sadler, G B. (2010). The States of Nature in Hobbes’ Leviathan (2010). Government and History Faculty Working Papers. 9. https://digitalcommons.uncfsu.edu/govt_hist_wp/9

Takyi, S. A., Amponsah, O., Darko, G., Peprah, C., Apatewen Azerigyik, R., Mawuko, G. K., & Awolorinke Chiga, A. (2022). Urbanization against ecologically sensitive areas: effects of land use activities on surface water bodies in the Kumasi Metropolis. International Journal of Urban Sustainable Development, 14(1), 460–479. https://doi.org/10.1080/19463138.2022.2146121

Terry, S (2019) International Monetary Fund Structural Adjustment Policy and Loan Conditionality in Ghana: Economic, Cultural, and Political Impacts. UVM Honors College Senior Theses. 319. https://scholarworks.uvm.edu/hcoltheses/319

Tom, M. N., Sumida Huaman, E., & McCarty, T. L. (2019). Indigenous knowledge as vital contributions to sustainability. International Review of Education, 65(1), 1-18. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11159-019-09770-9

Yahaya, A.-K. (2012). Indigenous knowledge in the management of a community-based forest reserve in the wa west district of ghanA Abdul-Kadiri Yahaya. Ghana Journal of Development Studies,, 9(1), 101-114. https://doi.org/10.20508/ijrer.v9i1