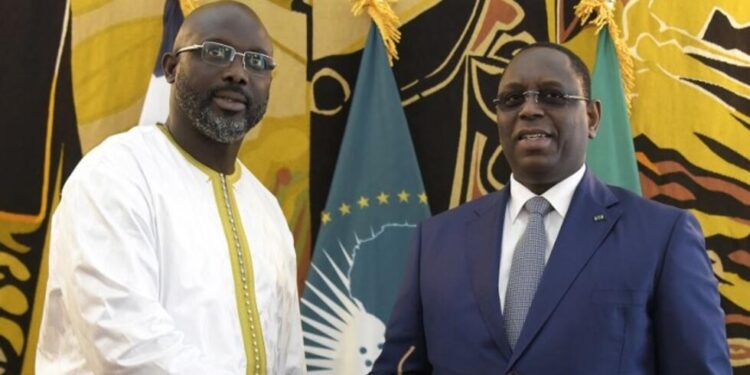

In July this year (2023), President Macky Sall of Senegal, who was first elected in 2012 and re-elected in 2019, announced he won’t be running for a third term in 2024, despite being goaded by his supporters to defy the West African country’s Constitution. He had promised in 2019 that he would serve his second and final term. Senegal’s Constitution has a two-consecutive-term presidential limit. Sall’s sanctioning and conviction of some members of his party, who had earlier opposed his candidature, was seen as a harbinger of his desire to go the Abdoulaye Wade way – attempt a third term – but his July announcement put that speculation to bed. One other reason that made Sall’s announcement surprising was that despite the two-consecutive-term limit of the Constitution, he had argued that he had the legal right to stand again once a review of that law had happened. In his view, such a revision would have reset his two terms to zero, starting from 2019. “I never wanted to be held hostage to this permanent injunction to speak before the hour,” Sall said in his national address where he made the announcement, explaining and justifying his decision: “I have a code of honour and a sense of historical responsibility which command me to preserve my dignity and my word”.

Sall’s Political Career

Sixty-three-year-old Sall, a geologist, was born on December 11, 1961, in Fatick, Senegal. Before becoming president, he served as the country’s prime minister from 2004 to 2007 under President Abdoulaye Wade. Coming from a modest family of five children, Sall studied geological engineering and geophysics at the University Cheikh Anta Diop in Dakar where he graduated in 1988. He also went to the French Institute of Petroleum outside Paris. In 2000, he became a special adviser on energy and mines. He later became minister of mines, energy, and water in 2001. In 2002, he became mayor of his hometown, Fatick, in addition to a stint as the one in charge of infrastructure and transportation. He later became a minister of state that year. Subsequently, he became minister for the interior and local government in 2003. The following year, Sall was appointed deputy secretary-general of Wade’s Senegalese Democratic Party (Parti Démocratique Sénégalais; PDS). He also became Wade’s fourth prime minister after the dismissal of his predecessor, Idrissa Seck.

Sall resigned from that position in 2007. He subsequently got elected as president of the National Assembly, as part of the Sopi Coalition, which won Wade the presidency in the 2000 presidential election. However, his audacity to summon his mentor’s son, Karim Wade, the President of the National Agency of the Organisation of the Islamic Conference (OIC), for an audit hearing in the National Assembly regarding construction sites in Dakar for the OIC Summit planned to take place there in March 2008 brought him to prominence. This move, interpreted by some analysts as a move by Sall to thwart the possibility of Karim becoming his father’s successor, earned him disaffection within the PDS. Infuriated by Sall’s daring action, leaders of the party voted to abolish his position as the second-most-powerful man within the party.

Also, and rather coincidentally, the National Assembly voted to cut from five years to just a year, the term of the Assembly’s presidency, in an obvious move to oust Sall. Still, a stubborn Sall wouldn’t budge until the Assembly passed a resolution to remove him. After clearly seeing the signs on the wall, Sall, who had been Wade’s protégé all these years, resigned from his mentor’s PDS to form his party, the Alliance for the Republic—Hope (Alliance pour la République—Yaakaar; APR—Yaakaar), along with some 30 ex-officials of Wade’s PDS. In 2009, he got re-elected as Fatick’s mayor on his new party’s ticket. Sall would quickly capitalise on his former mentor’s dwindling popularity and political fortunes, to have a shot at the presidency.

Amidst intense disillusionment by Senegalese over the rising cost of living, poor infrastructure, development dearth, and Wade’s quest for a third time seven-year term, Sall’s popularity soared, giving him a shot in the arm in the first round against Wade in February 2012. He trailed his former mentor-turned-arch rival’s 35 per cent with 27 per cent of the votes cast. Realising that Sall was within an arm’s length from the presidency, other opposition candidates threw their weight behind him in a concerted alliance aimed at constitutionally ousting Wade and thwarting his attempt at unconstitutionally staying in power beyond the two-consecutive-term limit. The opposition support increased Sall’s popularity, helping him to trounce Wade in the March run-off. His victory was a landslide, winning 66 per cent of the votes cast to Wade’s 34 per cent.

Sall’s Presidency

After his inauguration into office as the fourth president of Senegal on 2 April 2012, Sall wasted no time at all in cutting down the presidential cabinet to save the nation some much-needed funds. He scrapped some ministerial privileges and abolished 59 commissions and directorates he saw as unnecessary. Some of those state institutions included the National Agency of Senegal’s New Harbours; The Directorate of Small Aircraft Construction; The National Agency of the Desert High Authority; The Senegalese Office for Industrial Property and Technology Innovation, which overlapped with the Senegalese Agency for Industrial Property and Technology Innovation. He also had Wade’s management of the country audited. As part of his quest to fight corruption, Sall brought back life into the Court for the Repression of Illicit Enrichment while creating a National Anti-Corruption Office as well as a National Commission for Property Restitution and Recovery of Ill-Acquired Gains. Sall’s government also announced a price reduction on oil, rice, and sugar, as part of measures to reduce the cost of living for ordinary citizens while raising pension payments.

Also, peasants received emergency subsidies. Sall also set about to give life to one of his key campaign promises, which was to cut the term of a president from seven years to five years; and also limit a president to two terms. He submitted his proposals to the Constitutional Council in January 2016. The Council, however, rejected Sall’s quest to cut short his presidential term, but the other proposals, including the presidential term reduction that was to take effect after he left office, were allowed to be put to a referendum, which was held in March. More than 60 per cent voted in favour of the changes. One of his key projects is the ambitious construction of Diamniadio – a well-planned city that is intended to ease the activity burden on the overcrowded national capital Dakar, as part of his ‘Emerging Senegal’ ambition to transform the country. In 2019, Sall won a second term with 58 per cent of the vote in the presidential election held on February 24.

George Weah

Sall’s magnanimity has trickled down to his younger counterpart George Weah of Liberia. In the country’s recent national election, Mr Joseph Boakai, a former Vice President to Ellen Johnson Sirleaf, defeated Mr Weah, the incumbent, by a margin so small that in some other electorally volatile African countries, would have sparked civil dispute and, perhaps, even plunged them into war. Boakai, 78, won the November 14, 2023, runoff by 50.64 per cent of the votes cast, against the ex-football icon’s 49.36 per cent after neither of them got more than 50 per cent in the first round. The vote difference was a mere 20,567. Even though Weah was the loser, he won the hearts and minds of millions around the world with his easy concession. “A few moments ago, I spoke with president-elect Joseph Boakai to congratulate him on his victory,” Weah said on national radio, adding: “I urge you to follow my example and accept the results of the elections.” Had it been in some other volatile African country that statement would have easily read: “I don’t agree with the election results which I deem null, void and of no consequence”. Weah, however, rose to the occasion and proved himself a different brand of African politician. His political sportsmanship is the only reason why Liberia’s election has not been “worthy news” for the Western media. Weah took the sports spirit into politics and used it to tame storms.

Born on 1 October 1966 in Monrovia, Liberia, the 57-year-old African, European, and World Player of the Year in 1995, has always been a towering figure in his country and on the global stage even before entering politics. Weah, through his pre-political activism, used his international stature as a football icon, to help end a long civil war in his home country. He was later elected to the Senate in 2014. He first won the presidency in January 2018 as the 25th president of Liberia. He will be handing over to Boakai next year.

From Football to Politics

Liberia’s 24th President rose from the dusty streets of Monrovia to become a football legend. Starting with local teams in Liberia, he played for top clubs in Europe, including AS Monaco and AC Milan, earning numerous awards. Weah also played a crucial role in Liberia’s national team and became a UNICEF Goodwill Ambassador. Transitioning to politics, Weah faced challenges in presidential elections in 2005 and 2011 before winning a Senate seat in 2014. In 2017, he won the presidential election, marking Liberia’s first peaceful transfer of power in decades. Weah, a humanitarian, reduced his salary and contributed to peace efforts during Liberia’s civil crisis. However, in a surprising turn, Weah conceded defeat in the 2023 elections to Joseph Boakai, fostering a smooth transition and demonstrating a commitment to democratic principles. Weah’s journey reflects his dedication to both sports and public service in Liberia.

Lessons For Other African Leaders

Both Sall and Weah have proven to be a different breed of African politicians. They have a lot of bad examples on the continent to choose from but intentionally and voluntarily decided to carve a different narrative. They could have chosen to hold on to power just as their senior counterparts have done, as they are spoilt for choice in that department: They could have been a Teodoro Obiang Nguema Mbasogo (44 years in power), or a Paul Biya (41 years in power), or a Mobutu Sese Seko – late (32 years in power), or a Robert Mugabe – late (37 years in power), or a Gnassingbé Eyadéma – late (38 years in power) or a Jose Eduardo dos Santos – late (38 years in power), or a Denis Sassou Nguesso (37 years in power), Yoweri Musevi (36 years in power), Idriss Debby – late (31 years in power), Isaias Afwerki (30 years in power).

The narrative in most African countries is not a pleasant one, so, for a one-term president like Weah to gracefully concede and voluntarily urge his supporters to accept the results of the election, is highly commendable. Likewise, for Sall, who has yet to complete his second term, but has voluntarily announced that he does not intend to go the way of his predecessor. They are departing from the old order. They have their countries’ interests at heart. They have demonstrated their selflessness and shown that the bigger picture matters more to them than their interests.

Security Implications

Such voluntary concession and the decision not to go for an extra-constitutional term automatically relax internal tensions and de-escalate political acrimony. It also discourages and neutralises any intentions of coup makers or assassins who may be planning to annihilate the leader. It also reinforces their countries’ dedication to the tenets of democracy, thus, helping to maintain bilateral relations with Western democracies who are major donor partners. This ensures that the wheels of those countries’ economies do not grind to a halt since they avert sanctions and remove the risk of being side-lined economically. Furthermore, just as coups can be infectious, democratic behaviour can influence neighbour countries to follow their footstep, thus, gradually helping to entrench democracy in the sub-region. Where there’s peace and less tension, there is bound to be infrastructural development and jobs for the youth to beat down unemployment and idleness which are the main drivers of radicalism, terrorism and crime in most countries. It also ensures that the progress made by the previous government is not disrupted. Additionally, there is peace for agricultural activity to ensure food security and, avert famine, malnutrition and unnecessary loss of life. Weah and Sall are the new crop of leaders Africa needs. They are Africa’s sure bet to prosperity, peace, tranquillity, harmony and progress. Africa needs a lot more Salls and Weahs to go far and catch up with the West and change the face of the continent.

Source: CISA Analyst