Introduction

Policy influencing is either top-down or bottom-up, depending on the issues and who the key champions are. Education policies are key public initiatives meant to impact and shape the youth of Ghana into adults who become the next generation of leaders. Public policy, therefore, is a statement of prescriptive intent.[1] However, the intent for any sector cannot be determined by any one group of people or persons. Education is complex, with many stakeholders whose views must be taken into account before implementation.

The United Nations Educational Scientific and Cultural Organisation (UNESCO) believes that ‘education is a complex system with many interconnected subsystems and stakeholders. Any decision taken on one component at one level of education brings change to other components and subsystems. This interconnectedness requires policy and decision-makers to ensure that coherent and consistent education policy and strategic frameworks are in place from a sector and system perspective. Emerging challenges such as rapid digitalization, increasing inequality and disruptions caused by climate change, pandemics and conflicts, demand that countries develop resilient and sustainable policies and strategies on which to build efficient, relevant and transformative education systems.’[2]

In the last couple of years, the Republic of Ghana has taken on the challenge to digitalise as a major public policy initiative to ensure overall inclusiveness and grant greater access to services for the vast majority of its citizens. In the education sector, this has found expression in the Computerised School Selection and Placement system which has centralised the selection process for students moving from junior to senior high schools as well as several such initiatives.

The implementation of the Free Senior High School (SHS) was the result of a party manifesto by the NPP that gained significant traction and led to lots of discussion at various fora.

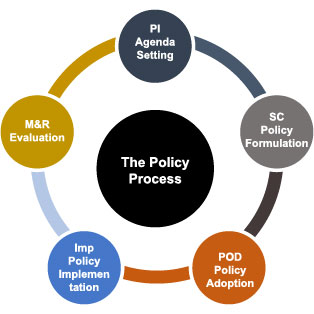

The Policy Process

The Policy Process is encapsulated in the policy cycle diagram below.

From the diagram above the policy process begins with the identification of an issue that is of critical importance or relevance. Then comes the stakeholder consultation to discuss issues and options, followed by the adoption of the best option for implementation. The policy is then implemented, monitored and evaluated for outcomes and impacts. It must be noted that at all stages of the process, discussions would need to be made relative to financial implications, the development of goals and objectives and a communication strategy to accompany policy implementation.[3] The above outline is a simplified one but essentially all relevant issues are taken into consideration including the financial, legal, gender and other relevant implications at the pre-implementation stage.

The Free SHS was a major political party policy initiative which was outlined to impact young people and provide them with an opportunity to attain secondary education at no cost. There have been criticisms that there was little depth in the consultative process to make the implementation more practical and sustainable in the long term. The reality of this criticism is discussed as follows.

The Ghanaian government made free, mandatory, basic education a constitutional necessity to bridge the achievement gap between the wealthy and the deprived. The Free Compulsory Universal Basic Education (FCUBE) initiative, which was first implemented in 1995, set a deadline of 2005 for achieving education for all[4].

This policy covers eleven years of universal basic education, which are divided into two years of kindergarten, six years of elementary school and three years of Junior High School. Such measures resulted in a long-term, unprecedented increase in the number of students enrolled, even from family members, because parents were no longer required to pay for their children’s education[5].

As part of the government’s policies to reduce and control this financial burden on the family unit, the Free Senior High School policy was introduced by the government in 2015 as a positive step for Ghanaians[6].

This progressively Free Senior High School Policy was a way for the government to partially support education at the Senior High School level. Some educational expenses, including exam fees, entertainment fees, library fees, dues for the Students Representative Council (SRC), sports and culture fees, science development fees, math quiz fees, and co-curricular fees to mention but a few, were waived for parents[7]. To end parents’ financial hardships when paying for their children’s tuition, the Ghanaian government converted from a progressively free senior high school policy to a free senior high school policy in 2017.

As a result, on September 12, 2017, the administration introduced the mandatory Free Senior High School Policy. This means the government absorbs all costs associated with attending public senior and vocational high schools, including boarding expenses, textbook costs, meal expenses, and other expenses[8].

What has been the impact

According to statistics, the Free SHS educational program has benefited over 1.6 million school children as of the end of 2021 since it began in 2017[9]. Similar to this, 2.2 million school children enrolled in the Free SHS after the 2022 school selection and placement process. Consequently, the Ghana Education Service (GES) launched the Double Track (DT) system in September 2018 as a transitory means of increasing enrollment without making equivalent infrastructural improvements[10].

The International Monetary Fund (IMF) has named the Free Senior High School policy to be among the outstanding social and economic reform programs that directly impact senior high school families and pupils. Particularly, parents and legal guardians have been exempted from responsibility for their obligations[11].

The Double Track system was created to address the challenges of increasing student enrollment and sparse infrastructure in many of the nation’s top senior high schools. The double-track system was an innovation that made it possible for schools to house more students in the same space, hence reducing overcrowding. The system separates all students and staff into two tracks, with one track attending classes while the others are on vacation, and vice-versa.

Since senior high school became free for all students in Ghana, enrolment has surged by 50%[12]. This is important for Ghana’s growth since mass education improves living standards. It promotes innovation and ideas with the potential to significantly increase productivity. Finally, the advantages of free education in Ghana go beyond simply relieving parents’ financial burdens.

The Challenges

There have been a number of challenges relative to the implementation of an otherwise good policy. They include the following:

1. The high financial burden on the state. The cost of the free SHS is huge. It has been argued that the policy could have been moderated in its implementation by making the parents bear the cost of boarding and lodging while all other costs remained free.

2. The large number of students being enrolled has put pressure on the facilities available to receive all students. The influx of students suddenly entering boarding houses, in particular, has raised security concerns for their health and well-being. While the ‘double-decker’ beds were the order of the day, the incidence of three-level beds in boarding houses is testimony to the overcrowding and lowering quality of education[13].

3. The large number of students entering SHS has also put a toll on teachers, worsened by the double track system, which has effectively ensured that some teachers do not have a vacation at all. This is leading to teacher burnout and has been a source of concern for the teacher unions which have complained about this.

4. The large number of students on small campuses has had implications for discipline. On the one hand, the GES has been very strict with teachers who mete out corporal punishment, standardised haircuts and other forms of disciplinary measures as a way of ensuring sanity on campuses. However, the attitude of the GES has ensured that teachers do only what is expected of them, leading to falling standards in discipline.

5. The large numbers have also led to inadequate teaching and learning materials, impacting the quality of education[14].

6. There have been challenges with support to the schools leading to some heads reportedly charging illegal fees. This has led to further financial challenges for families and undermined the policy’s overall purpose[15].

Recommendations

· In an age of digitalisation, it is crucial to expand the frontiers of education through the use of digital platforms and devices. It is understood that the Centre for Distance Learning and Open Schooling (CENDLOS) has developed mobile devices on which educational material is stored. This would make it possible to reach a wider audience irrespective of geographical location. Additionally, it would support the same quality in terms of delivery.

· Due to the heavy financial burden on the government, it is recommended that the boarding and lodging costs should be fully borne by parents who want their children to enjoy that.

Conclusion

Addressing these concerns is crucial for ensuring that the Free Senior High School Policy in Ghana achieves its intended purpose of increasing access to education while maintaining security and quality. To implement this policy effectively, there would be the need to undertake an in-depth evaluation to outline the needed critical investments to make a difference.

[1] See p 17 of the NDPC guidelines at

[2] See unesco.org education policies

[3] See p 34 of the NDPC document on steps to policy development accessed

[4] Kwame Akyeampong, “Revisiting Free Compulsory Universal Basic Education (FCUBE) in Ghana,” Comparative Education 45, no. 2 (2009): 175–95.

[5] Abdul-Rahaman et al., “The Free Senior High Policy: An Appropriate Replacement to the Progressive Free Senior High Policy.” International Journal of Education and Literacy Studies 6, no. 2 (2018): 26–33

[6] Gabriel Asante and David Agbee, “Responding to Access and Beyond in Fee-Free Policies: Comparative Review of Progressive Free Senior High and Free Senior High School Policies in Ghana,” Science Open Preprints, 2021.

[7] Shadrack Osei Frimpong et al., “Towards a Successful Free Senior High School Policy in Ghana: The Role of Non-Profit Organisations,” Voluntary Sector Review, 2022,1-12

[8] Kyei-Nuamah David and Larbi Andrews, “Free Senior High School Policy in Ghana: Implementation and Outcomes

against Policy Purposes,” International Journal of Trend in Scientific Research and Development 6, no. 6 (2022): 1207–22

[10] Ghanaian Times, “Free SHS Has Increased SHS Enrolment by 50% – Bawumia,” May 27, 2022

[11] John Osae-Kwapong, “IMF Support: Free SHS Worth Saving,” Graphic Online, July 16, 2022

[12] Ghanaian Times, “Free SHS has increased SHS enrolment by 50% – Bawumia.”

[13] Asumadu, E. (2019). Challenges and prospects of the Ghana Free Senior High School (SHS) Policy: The case Of SHS in Denkyembour District, Thesis, University of Ghana

[15] African Development Fund (2003). Republic of Ghana development of senior secondary education project (education iii) appraisal report.

Source:

Joseph K Aning

Joseph K Aning is a fellow at the Centre for Intelligence and Security Analysis. His main interests are in the area of Economic History and Education.

Samuel Aning

Sam is an Associate at CISA. His interests include political risk analysis, country studies and international law.

Nana Akua Sarpomaa Nimako-Boateng

Nana is a researcher with interests in public policy, monitoring and evaluation.