Introduction

Security issues on the African continent have long been enforced and reinforced by different but closely interrelated factors. These include historical legacies rooted in colonialism, socio-political structures, and economic conditions. However, one of the most critical issues in contemporary African security discourse and analysis is the phenomenon of security contagion. It details how insecurity spreads from one region to another, mostly driven by conflict, terrorism, political instability, and other destabilising factors. While much has been written on security contagion in general, its gendered dimensions remain underexplored. In this write-up, CISA analysts seek to fill this gap by examining how security contagion in Africa is shaped by and impacts gender relations, with a focus on how women and men experience and respond to insecurity differently.

Understanding Security Contagion in Africa

In the June to August editions of CISA’s monthly articles, CISA analysts, driven by the current spread of insecurity to other regions on the continent, decided to explore the concept of security contagion to draw the attention of relevant stakeholders and also to inform further empirical research to help curb the menace. CISA analysts, framing the phenomenon through the lens of systems theory in the June edition, argued that security contagion in the continent results from porous borders, weak state institutions, and other factors. Countries in the Sahel, which are now considered epicentres of violent deaths, have experienced significant spill-over of violence and insecurity, reinforced by the proliferation of small arms, the rise of extremist ideologies, and the entanglement of local conflicts with global geopolitical actors, like the shifting alliance between Russia and the Alliance of Sahel States.

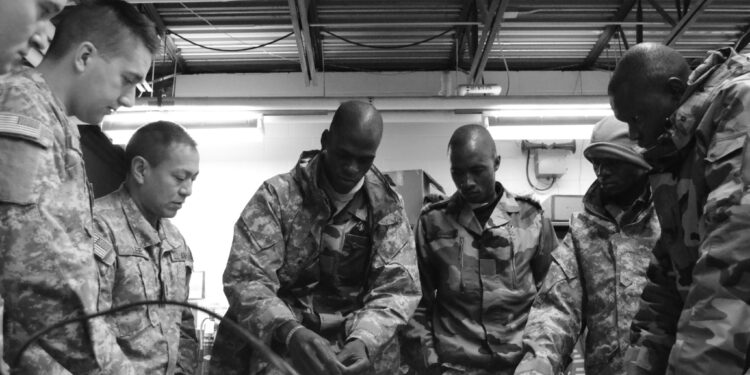

CISA analysts argue that traditionally, the discourse on security contagion focuses on state-centric issues like the call for military interventions, peacekeeping efforts, and counterterrorism strategies. However, this state-centric approach often overlooks the socio-cultural and gendered dimensions of security, which are crucial for understanding the full impact of contagion.

The Gendered Nature of Insecurity

Many African societies are still very conservative; as a result, gender roles are deeply entrenched, affecting how men and women experience and respond to conflict. In times of insecurity, these roles are often amplified, with specific expectations placed on both men and women, shaping their lived experiences in terms of violence, displacement, and survival.

Men are mostly seen as the key actors in conflict, either as combatants or protectors. This stems from traditional gender norms that associate masculinity with strength, aggression, and the defence of the community. In the context of security contagion, males, irrespective of their age, are regularly recruited into armed groups, sometimes voluntarily and sometimes through coercion. The pressure to conform to these roles, which has been termed “toxic masculinity,” is illustrated by many proverbs, especially in the Akan language. Examples of such proverbs are: “Only a man can drink bitter medicine,” “When a gun is fired, it is the man who receives the bullet on his chest,” and “Even if a woman buys a gun or a drum, it is kept in a man’s hut.” (Akan proverbs translated into English).

These responsibilities placed on men during conflict can have profound psychological impacts. The inability of men to fulfil the role of protector, whether due to injury, displacement, or the overwhelming force of the enemy, can lead to feelings of shame and being labelled as “not man enough.” These emotions are often reinforced by the lack of mental health services in conflict zones, leaving many men to suffer in silence, which is another expectation in African societies.

While men fulfil their gender roles by being on the front lines of combat, women are mostly targeted in other ways, particularly through sexual violence. This includes rape, which is commonly used as a weapon of war to harm, humiliate, and destabilise communities. The prevalence of sexual violence in conflict zones is well-documented, especially by mainstream media platforms like BBC and CNN, but its impact on the broader dynamics of security contagion is less understood. Women in war zones are often framed as victims, but it is important to note that they also play critical roles as resilient agents of survival and peacebuilding. These women often take on the roles of providing for their families, navigating displacement, and maintaining social cohesion in the face of ongoing violence, reflecting their triple roles of production, reproduction, and community management (see Moser, 1993). Despite these contributions, women are often not involved in formal peace processes and not engaged in decision-making structures, limiting their ability to influence the resolution of conflicts that disproportionately affect them.

The Intersection of Gender and Security Contagion

The gendered dynamics of security contagion are complex and multifaceted. For instance, the spread of extremist ideologies often comes with the imposition of rigid gender norms that further marginalise women and negatively impact men as well. In areas under the control of extremist and insurgent groups, women are forced into early marriages, denied access to education, and subjected to strict dress codes and behavioural restrictions. Men, particularly young men, are often forced to take up arms and fight in conflicts, but this is not often discussed. These gender-specific impacts of security contagion have long-term implications for men’s and women’s rights and gender equality. Moreover, the displacement caused by security contagion often exacerbates existing gender inequalities. Refugee camps, as well as settlements for internally displaced persons (IDPs), are frequently sites of gender-based violence, including domestic abuse, sexual exploitation, and human trafficking. The breakdown of social structures in these settings leaves both males and females vulnerable, with limited access to protection and support services.

Conclusion Addressing the gendered dynamics of security contagion in Africa requires an integrated approach. When we talk about gender, it is important to note that it is not just limited to women or girls but also includes boys and men. It is incorrect to frame only women and girls as vulnerable in war zones while men and boys are not seen as such. Even among women, there are differences and power dynamics, meaning women do not have the same lived experiences, making it incorrect to box them all as vulnerable. Though differently, both men and women are affected by security contagion, and policies must target all of them. As a result, more research is needed to understand the gendered dynamics of security holistically so that no gender is left behind or marginalised due to established cultural norms as we strive for a better Africa.