Introduction

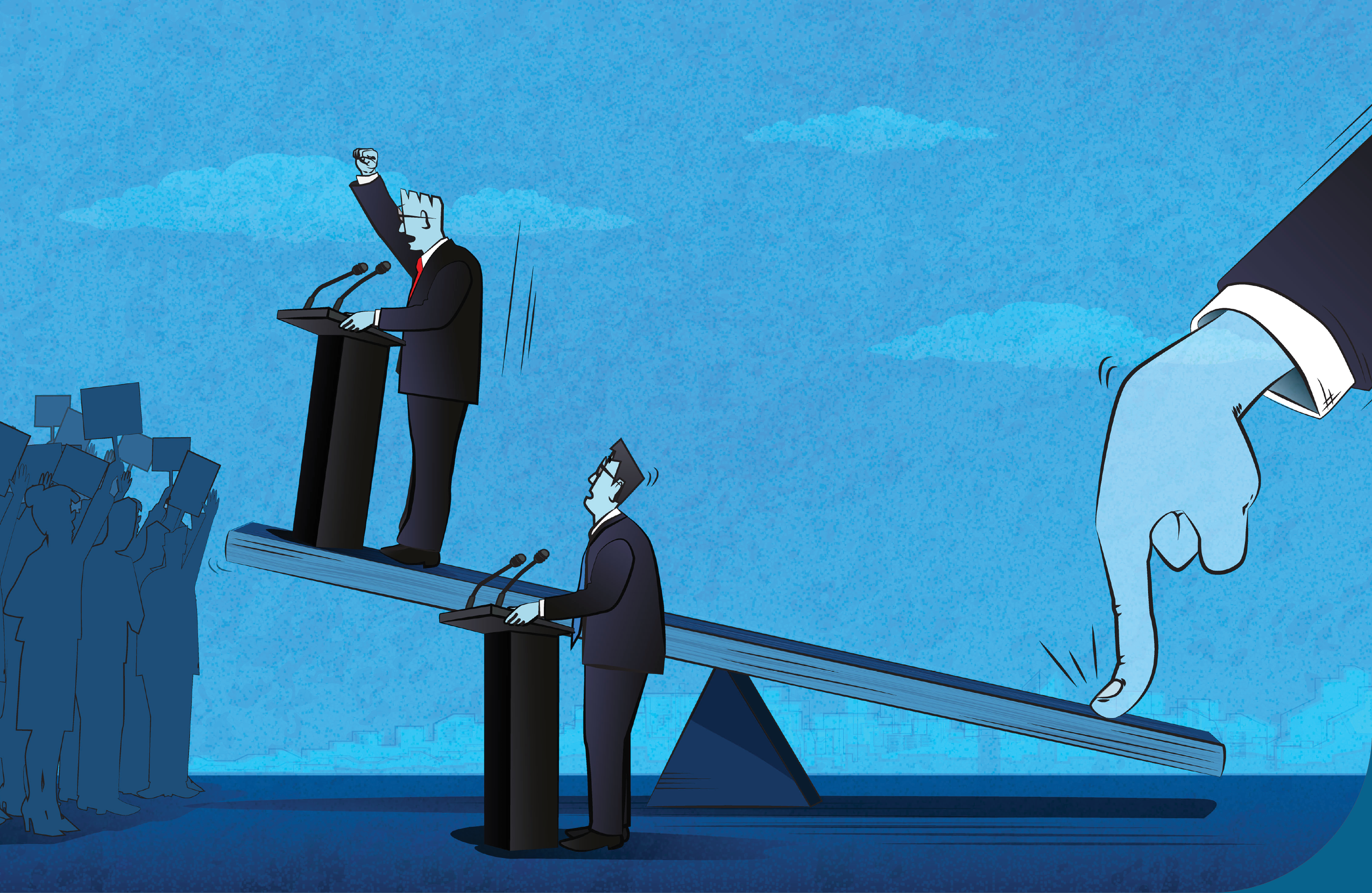

Across the history of African development, the continent has remained a site of competing interests clothed in the rhetoric of benevolence as well as partnership The term maligned interest captures a subtle but enduring dynamic, the pursuit of self-serving objectives by actors who present themselves as allies of African progress (Flashpoint, 2021; Wagnsson, 2020). These interests, both external and internal, manipulate narratives of aid, development, and modernisation while entrenching dependency and inequality (Kay, 2011; Kumi, 2020; Tomohisa, 2001). From the colonial encounter since the 15th century to the neoliberal present since the 1980s, Africa’s developmental trajectory has been repeatedly shaped by actors whose motives are disguised as reformist but whose outcomes reproduce marginalisation (Brenner & Theodore, 2005; Nkrumah, 1965; Rodney, 1972).

As part of the Centre for Intelligence and Security Analysis (CISA)’s preparation for the Second Edition of the High-Level Security Conference, this article explores the historical and contemporary manifestations of maligned interests in Africa. It argues that the continent’s underdevelopment and fragmented progress are sustained not only by global capitalist structures and geopolitical rivalries but also by domestic elites who collaborate with external powers to perpetuate systems of extraction, dependency, and control. The theme invites critical reflection on how such interests undermine Africa’s sovereignty, distort its security and development priorities, and shape the continent’s place within an unequal global order.

2. Historical Roots and Contemporary Manifestations of Maligned Interest

The origins of maligned interest in Africa can be traced to colonialism (Rodney, 1972). Colonialism was legitimised through paternalistic discourses of civilisation and progress, which concealed the economic imperatives of resource extraction and territorial control. European powers justified their conquest under the guise of a moral duty to uplift and civilize Africans, an ideology epitomised by Rudyard Kipling’s poem “The White Man’s Burden” (Murphy, 2010) and Lord Lugard’s “The Dual Mandate in British Tropical Africa” (1922). Both writings framed imperial domination as a benevolent enterprise aimed at development, yet the underlying intent was the systematic exploitation of the colonies’ land, labour as well as minerals.

Following independence, this pattern of domination did not disappear; rather, it evolved into new and more subtle forms of dependency expressed through unequal trade relations, foreign aid conditionalities, and debt accumulation (Frank, 1991; Moyo, 2009; Nkrumah, 1965). The postcolonial state, constrained by the global capitalist order and often complicit political elites, became enmeshed in structures that continued to privilege external interests over domestic autonomy. Thus, the colonial logic of extraction was rebranded in the language of development and modernisation, maintaining Africa’s subordinate position within the international economic hierarchy. The Structural Adjustment Programs (SAPs) imposed by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank in the 1980s exemplify this postcolonial continuity. Framed as necessary for economic reform, SAPs required austerity measures, privatisation, and the liberalisation of markets (Ogola, 2025). In practice, these policies dismantled social safety nets, weakened state institutions, and opened African economies to foreign domination. As Mkandawire (2001) and Rodney (1972) observe, African states were restructured to serve the logic of global capitalism rather than domestic development. The complicity of African political elites further reinforced this pattern, as many became intermediaries who facilitated the flow of capital and resources outward in exchange for personal or political gain.

In the 21st century, the nature of maligned interest has diversified but not diminished. The geopolitical competition among global powers, particularly China in the 2010s, the United States and the European Union, has redefined Africa’s role in international relations. While China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) is often portrayed as a partnership for infrastructure development, it has simultaneously deepened Africa’s debt exposure and revived concerns of neocolonial dependency (Ajah & Onuoha, 2025). Western governments, on the other hand, continue to wield influence through aid programs and security interventions that prioritise their strategic interests over Africa’s autonomy. Beyond state actors, multinational corporations have become central to this web of maligned interests. The operations of extractive industries in oil, gold, and cobalt reveal a pattern of profit repatriation, environmental degradation as well as local impoverishment. For instance, Ghana’s gold and oil sectors remain dominated by foreign firms whose operations are enabled by local elites through opaque contracts and regulatory capture. Similarly, in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), the global demand for cobalt, essential for renewable energy technologies, has produced labor exploitation and displacement, underscoring the irony of “green” development built on African suffering.

4. The Political Economy of Maligned Interests and Consequences for Development and Sovereignty

The persistence of maligned interests in Africa can be understood through the lens of dependency theory and critical political economy. Dependency theorists such as Walter Rodney have long argued that the global capitalist system is structured to keep African economies peripheral, supplying raw materials while importing finished goods and technologies. This structural relationship ensures that Africa remains a supplier of value rather than a beneficiary. Moreover, governance frameworks in many African countries have been shaped to accommodate external pressures. The neoliberal reforms of the 1990s promoted privatisation and deregulation, often at the expense of social equity and institutional accountability. The result is what Ferguson (1994) calls the “anti-politics machine,” where development projects depoliticise structural inequalities and mask power relations under technical language. Weak institutions, corruption, and elite capture thus create fertile ground for the entrenchment of maligned interests.

The consequences of these dynamics are profound as maligned interests have sustained economic dependence, undermined democratic accountability, and eroded sovereignty. African states often find themselves balancing between donor expectations and domestic needs, leading to policies that privilege external validation over internal legitimacy. The environmental cost is equally devastating. Deforestation, pollution, and resource depletion continue in the name of development. Socially, inequality widens as wealth becomes concentrated among political elites and foreign investors, leaving the majority in precarious conditions. Perhaps, the most insidious effect is the loss of epistemic sovereignty. Africa’s development discourse remains heavily influenced by external frameworks that define progress in Western terms. This intellectual dependency shapes education, policy-making, and even imagination, limiting the space for indigenous knowledge systems and alternative development paradigms.

Despite these constraints, Africa is not without agency. The resurgence of Pan-Africanist thought and youth-led movements signals a growing rejection of imposed narratives. Movements such as #EndSARS in Nigeria, #FeesMustFall in South Africa, the Saheleian coups of the 2020s and climate activism across the continent reflect a new generation’s insistence on justice, transparency and self-determination. Regionally, initiatives such as the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) and the reform of the African Union represent efforts to reclaim economic sovereignty and foster intra-African collaboration. However, for these initiatives to succeed, they must be accompanied by governance reforms that dismantle elite capture and ensure that the benefits of development are equitably distributed. Reimagining development from within, rooted in African values, ecological balance, and social justice is essential to breaking free from the cycle of maligned interests.

The persistence of maligned interests in Africa reflects a structural and ideological struggle over power, knowledge, and resources. While the forms of exploitation have evolved from colonialism to neoliberalism to digital dependency, the underlying logic of domination remains. True transformation requires more than economic reform; it demands a radical rethinking of Africa’s place in the global order and the cultivation of an autonomous vision of development. In the medium term, confronting external manipulation and internal complicity calls for pragmatic and collective action. African governments must strengthen regional economic blocs and deepen trade under the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) to reduce reliance on external actors. Ghana and other African states should invest in technological sovereignty by supporting local innovation, data protection frameworks, and digital literacy programs that resist new forms of dependency. Equally important is nurturing accountable governance, curbing elite capture, promoting transparency, and empowering civil society to hold leaders to ethical standards. By reorienting policies toward self-determination, inclusive development, and institutional integrity, Africa can chart a future grounded in sovereignty, dignity, and collective progress.

Reference

Ajah, A. C., & Onuoha, J. I. (2025). China’s Belt and Road Initiative and Infrastructure Development in Nigeria: Unveiling a Paradigm Shift or Repackaging of Failed Ventures?. Journal of Current Chinese Affairs, 54(2), 119-148. https://doi.org/10.1177/18681026251330645

Brenner, N., & Theodore, N. (2005). Neoliberalism and the urban condition. City, 9(1), 101–107. https://doi.org/10.1080/13604810500092106

Ferguson, J. (1994) The Anti-Politics Machine: Development, Depoliticization, and Bureaucratic Power in Lesotho. University of Minnesota Press, Minneapolis.

Flashpoint ,. (2021). What Is Malign Influence and How Can OSINT Address It? | Flashpoint. Flashpoint. October 20, 2025. https://flashpoint.io/blog/malign-influence-osint/

Frank, A. G. (1991). The Underdevelopment of Development. Bethany House Publishers.

Kay, C. (2011). Andre Gunder Frank: ‘Unity in Diversity’ from the Development of Underdevelopment to the World System. New Political Economy, 16(4), 523–538. https://doi.org/10.1080/13563467.2011.597501

Kumi, E. (2020). From donor darling to beyond aid? Public perceptions of ‘Ghana Beyond Aid’. The Journal of Modern African Studies, 58(1), 67-90. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0022278x19000570

Luggard, F. D. (1922). The Dual Mandate in British Tropical Africa. Edinburgh and London: William Blackwood and Sons .

Mkandawire, T. (2001). Thinking about developmental states in Africa. Cambridge Journal of Economics, 25(3), 289-314. https://doi.org/10.1093/cje/25.3.289

Moyo, D. (2009). Dead Aid. Macmillan.

Murphy, G. (2010). Shadowing the White Mans Burden: U.S. Imperialism and the Problem of the Color Line. NYU Press. http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt9qgcc1

Nkrumah, K. (1965). Neo-Colonialism, the Last Stage of Imperialism. London: Thomas Nelson & Sons, Ltd.

Ogola, C. (2025). Structural Adjustment Programs (SAPS) and Social, Economic and Political Stability of the Least Developed Countries Since 1980s. International Journal of Research Publication and Reviews, 6(1), 968-975. https://doi.org/10.55248/gengpi.6.0125.0306

Rodney, W. (1972). How Europe Underdeveloped Africa. London: Bogle-L’Ouverture Publications.

Tomohisa, H. (2001). Reconceptualizing Foreign Aid. Review of International Political Economy, 8(4), 633–660. http://www.jstor.org/stable/4177404

Wagnsson, C. (2020). What is at stake in the information sphere? Anxieties about malign information influence among ordinary Swedes. European Security, 29(4), 397–415. https://doi.org/10.1080/09662839.2020.1771695