The proliferation of small arms and light weapons (SALWs) in West Africa is a major contributor to the region’s deepening insecurity. This dynamic fuels and sustains insurgencies, civil conflicts, and organised crime. West Africa, in particular, suffers from porous borders, weak state institutions, and post-conflict environments that create conditions conducive to arms trafficking. The region’s instability is both a cause and consequence of the proliferation of arms, producing a vicious cycle that is difficult to contain.

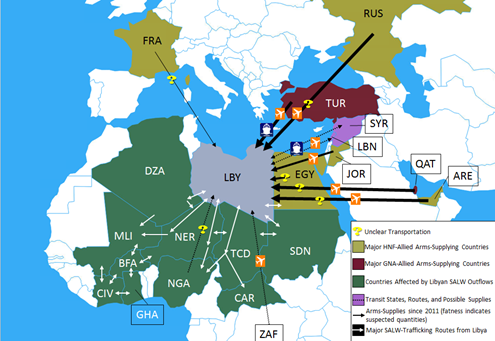

The fall of the Gaddafi regime in Libya in 2011 marked a turning point for arms flows across the Sahel and West Africa. During the four decades of Muammar al-Gaddafi’s rule, Libya became one of the most heavily armed states in Africa. After his overthrow in 2011, looting of weapons stockpiles led to a spread of arms within the country. Particularly, Small Arms and Light Weapons (SALW) proliferated to West African conflict zones and terrorist groups. In addition to the weapons looted from Gaddafi’s stockpiles, further weapons deliveries entered Libya, equipping the two major factions of the ongoing conflict, the UN-recognised Government of National Accord (GNA) and the Libyan National Army (LNA). The concurrent support of both – and several smaller and allied – factions mirror the complicated and internationalised status quo of the conflict (Schwarz, 2020).

Weapons from Libyan stockpiles, including assault rifles, anti-aircraft guns, and explosives, flooded into neighbouring states. These weapons reached insurgent and terrorist groups such as Al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM), the Islamic State in the Greater Sahara (ISGS), and Boko Haram, significantly enhancing their operational capabilities (UNODC, 2021). Empirical evidence from the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI) shows that many of these weapons are trafficked through Niger and Mali, exploiting poorly monitored trade routes and corrupt border officials (SIPRI, 2020).

In Burkina Faso, the expansion of jihadist violence has been strongly linked to the flow of illicit arms. Attacks on military outposts and civilian populations are often carried out using sophisticated weaponry, much of which originates from regional trafficking networks. The arming of volunteer defence forces by the government, while a necessary counterinsurgency measure, has contributed to further proliferation. Similarly, in Mali, various armed actors, including separatists, jihadists, and ethnic militias, have leveraged access to illicit arms to assert control over territory and challenge the state (Thurston, 2020).

Nigeria’s experience provides further insight into the impact of arms trafficking on regional security. Beyond the northeast, where Boko Haram operates, the north-central and north-western regions have experienced rising levels of communal violence and criminal banditry. According to Edeko (2011), the ready availability of firearms has intensified pastoralist-farmer conflicts and transformed local disputes into deadly encounters. Weapons are smuggled across porous borders with Chad, Niger and Cameroon, or diverted from poorly guarded security stockpiles. This has undermined internal stability and contributed to Nigeria’s broader governance challenges (Onuoha, 2013).

The implications of arms trafficking extend beyond immediate violence. Illicit arms flows undermine disarmament and peacebuilding efforts, weaken the legitimacy of state security forces, and increase the militarization of civilian spaces (Muggah, 2006). Community self-defense groups, often formed in response to state failure, have become both a symptom and source of insecurity. In many cases, such groups operate without formal oversight, leading to cycles of revenge violence and further destabilization (Florquin & King, 2018).

Regional efforts to curb arms proliferation include the ECOWAS Convention on Small Arms and Light Weapons, adopted in 2006. The convention mandates member states to control arms production, transfer, and possession. However, implementation has been hindered by limited institutional capacity, inconsistent enforcement, and political instability (Aning, 2005). Despite support from international donors and technical assistance programs, national compliance remains uneven across West Africa. Moreover, coordination among border security agencies is often weak, with intelligence-sharing mechanisms either underdeveloped or poorly resourced (UNREC, 2016).

To mitigate the spread of arms and the resulting instability, a comprehensive and cooperative approach is required. This includes investing in advanced border surveillance technologies, enhancing weapons marking, tracing and record-keeping, and strengthening regional intelligence-sharing systems. International actors can support these efforts by aligning aid with disarmament goals and providing sustained funding for capacity building.

As a result of the challenges enumerated above, the problem of arms trafficking requires a multi-faceted regional approach. ECOWAS must be involved and a regional approach would require intense diplomatic discussions to involve the AES countries where insurgents are most active. The local manufacture of SALW would need to be discussed vis-à-vis provision of alternative income-generating activities.

Ultimately, addressing arms trafficking in West Africa must be part of a broader strategy that tackles root causes of conflict, such as poverty, marginalisation, and weak governance (Karp, 2014).

References

Aning, K. (2005). The anatomy of Ghana’s secret arms industry. African Security Review, 14(4), 115-126.

Edeko, S. E. (2011). The proliferation of small arms and light weapons in Africa: A case study of the Niger Delta in Nigeria. Sacha Journal of Environmental Studies, 1(2), 55-80.

Florquin, N., & King, B. (2018). From legal to lethal: Converted firearms in Europe. Small Arms Survey.

Karp, A. (2014). Measuring the impact of firearms on violence. In Small Arms Survey 2014: Women and Guns (pp. 9-39). Cambridge University Press.

Muggah, R. (2006). No magic bullet: A critical perspective on disarmament, demobilization and reintegration (DDR) and weapons reduction in post-conflict contexts. The Round Table, 94(379), 239–252.

Onuoha, F. C. (2013). The state and management of religious violence in Nigeria: A case of the Boko Haram insurgency. African Security Review, 22(3), 45-52.

SIPRI. (2020). Arms flow to conflict zones: Lessons from Libya. Stockholm International Peace Research Institute.

Small Arms Survey. (2018). Estimating Global Civilian-Held Firearms Numbers. Geneva: Graduate Institute of International and Development Studies.

Schwarz, M. (2020). From Legal to Illegal Transfers: Regional Implications of Weapon Flows to Libya.

Thurston, A. (2020). Jihadists of North Africa and the Sahel: Local politics and rebel groups. Cambridge University Press.

UNODC. (2021). Firearms Trafficking in the Sahel. United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. UNREC. (2016). Assessment of the implementation of the ECOWAS Convention on Small Arms and Light Weapons. United Nations Regional Centre for Peace and Disarmament in Africa.