This year, 20 African countries were billed to hold presidential and parliamentary elections on different dates. They include: Comoros (14 January 2024), Senegal (originally billed for 25 February 2024 but was postponed on 3 February 2024 to 15 December by President Macky Sally, who later rescheduled it for 24 March 2024 following violent street protests), Togo (20 April 2024), Mali (originally scheduled for 4 February 2024 but has been postponed indefinitely by the military junta), Ghana (7 December 2024 for both presidential and national assembly), Madagascar (May 2024 – parliamentary), Rwanda (15 July 2024), Chad (6 May 2024 for the presidential election and October 2024 for the national assembly and local elections), Guinea Bissau (November 2024 for the presidential election), Algeria (December 2024 – presidential), Mauritania (22 June 2024 – both presidential and senatorial), Mozambique (9 October 2024 – presidential, national assembly and local elections), Mauritius (November 2024 – general elections), Botswana (October 2024 – National assembly and local elections), South Africa (29 May 2024 – national assembly and local elections), Namibia (November 2024 – both presidential and national assembly), South Sudan (December 2024 – presidential, national assembly and local elections), Somaliland (November 2024 – presidential), Tunisia (October 2024 – presidential) and Cabo Verde – local election.

These countries constitute 37 per cent of the continent’s 54 countries. Some 30% of the elections will be in Southern Africa with 25% in West Africa, 20% in North Africa, and 10% in Central Africa.

Comoros opened the election door on 14 January 2024. Incumbent President Azali Assoumani was declared the winner by the country’s electoral commission with 62.97% of the vote. The Supreme Court, however, validated only a win of 57.2 per cent of the vote. This raised suspicions of fraud, sparking street protests on the streets of the capital Moroni. The authorities declared a curfew to curtail the unrest.

Mali, which is currently being led by a junta, was supposed to have followed suit and held elections on 4 February 2024, to return the country to civilian democracy but that didn’t happen due to what the regime called “technical reasons.” Mali suffered two coups within nine months spanning 2020 and 2021. On August 18, 2020, President Ibrahim Boubacar Keïta was overthrown by the military, and a transitional government was formed in October of that year. However, on May 24, 2021, the military arrested the president and the Prime Minister. Colonel Assimi Goïta was inaugurated in June as transitional president. The Goïta-led junta promised to hold elections in February 2024 but that has still not happened. Currently, Mali has formed an alliance with Burkina Faso and Niger, both of which are also led by juntas who took power through coups. The Niger military took power by force on July 26, 2023, when the army announced the overthrow of President Mohamed Bazoum. General Abdourahamane Tiani became the new leader of the country. After the Niger coup, the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) threatened on August 10, 2023, to deploy a regional force to “restore constitutional order” in the francophone country.

Before the ousting of Bazoum in Niger, there had been two coups within a space of eight months in Burkina Faso – Ghana’s northern neighbour. The first one occurred on January 24, 2022, when President Roch Marc Christian Kaboré was removed from power by the military and Lieutenant-Colonel Paul-Henri Sandaogo Damiba was subsequently inaugurated president in February of the same year. On September 30, 2022, Lieutenant-Colonel Damiba, too, was at the receiving end of the bitter putsch pill when he was dismissed by the army and replaced by Captain Ibrahim Traoré as a transitional president until a presidential election scheduled for July 2024. In September 2023, however, Captain Traoré postponed the July 2024 election indefinitely, explaining that it was “not a priority”.

It is clear that these Three Musketeers of the Sahel – Niger, Mali, and Burkina Faso – do not intend to relinquish power to civilian democracy anytime soon, as they have allied, through which many joint major decisions that not only affect their countries but the entire region, have been taken.

The triad, who jointly formed the Alliance of Sahel States (AES), have put together a joint force to fight the very evil from which they collaterally benefitted – terrorism. Niger’s army chief Moussa Salaou Barmou made the announcement on Wednesday, 7 March 2024 following talks in his country’s capital, Niamey. All three countries have also cut ties with former colonial master France and exited the Economic Community of West African States, whose leaders they accused of siding with foreign powers and doing little in the anti-terrorism department. Additionally, they withdrew from the G5, an international anti-terrorism force before forming the AES – a closely-knit replacement. Furthermore, the leaders of the juntas ordered the UN peacekeeping mission in Mali, Minusma, which, for decades, was helping the security situation in the region, to pack out. But while cutting ties with some Westerners, they were strengthening ties with others such as Russia. Vladimir Putin and Russia’s Wagner Group, loom large in the economic, geopolitical and security affairs of the Sahel now, much to the chagrin of the West. The three military leaders are Putin’s Darling Boys. Any decision concerning the holding of elections in their respective countries would have to align with Putin’s interests and agenda in for the region and Africa as a whole.

Another junta-led administration in West Africa, Guinea, has promised to hold both presidential and legislative elections by the end of December 2024, as part of a 10-point transition roadmap negotiated with the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS). On September 5, 2021, the military overthrew President Alpha Condé and Colonel Mamady Doumbouya became president on October 1, 2021. Guinea would then return to civilian governance if the elections take place.

Guinea-Bissau, another West African country that is no stranger to political turmoil, also goes to the polls this year. According to the Africa Centre for Strategic Studies, Guinea-Bissau has experienced four coups and more than a dozen attempted coups while enduring 23 years of direct or military government since independence from Portugal in 1973. ACSS reports that President Úmaro Sissoco Embaló has dismissed Parliament twice in 2 years (including in December 2023) alleging coup attempts, which have contributed to government paralysis. The Centre observes that while the leading political parties have not officially put forward their candidates, the 2024 election could likely involve a rematch of the 2019 poll, where President Embaló gained 53.5 per cent of the vote versus Domingos Simões Pereira’s 46.5 per cent.

Per the electoral calendar, Senegal (considered a bastion of democracy in the sub-region), would have been the next to organise its February 25 polls after Mali, but for President Macky Sall’s unprecedented postponement of the elections to mid-December. His announcement sparked violent street protests in the national capital. He later rescheduled the elections to 24 March 2024 after the country’s Constitutional Council ruled that he had no authority to stay in power beyond his 2 April 2024 tenure. Sall was also accused by his opponents of staging a constitutional coup to perpetuate himself in power beyond the constitutional term limit even though he had explicitly and repeatedly said he was not going to run for a third term. The world now awaits the outcome of the 24 March elections. If all turns out well, Senegal would’ve successfully salvaged its reputation as a shining star of democracy in the turbulent sub-region despite the near-denting of that image by President Macky Sall’s faux pas.

Still in West Africa, another democracy giant, Ghana, will be electing a new president and parliament on 7 December 2024, as President Nana Akufo-Addo exits office on 7 January 2025 after serving two consecutive terms of four years. Ghana’s 1992 Constitution has a two-term limit. Ghana has had five democratic transitions of government since the beginning of its Fourth Republic in 1992. In his last State of the Nation Address, President Akufo-Addo said even though Ghana’s electoral system is not perfect, every election has been an improvement on the previous one. He also rallied Ghanaians to support the 1992 Constitution to entrench democracy in the country rather than go the coup way.

“Unconstitutional changes in government in parts of Africa, especially in West Africa, through a series of coups d’état and military interventions in governance, testify to an unfortunate democratic regression in the region”, the Ghanaian leader said, adding that it would be in the interest of democratic growth that this development is “reversed as soon as possible”, adding: “And we, in Ghana, continue to give maximum support to ECOWAS, the regional body of West Africa, and the African Union, Africa’s continental organisation, in their efforts to restore democratic institutions in the affected nations”. “We must help stem the tide of this unwelcome evolution, and help entrench democracy in West Africa. We believe also that a reform of the global governance architecture, such as the Security Council of the United Nations, to make it more representative and accountable, will help strengthen global peace and stability, and, thereby, help consolidate democratic rule in the world”, Mr Akufo-Addo noted.

The president recalled that Ghanaians have had “our fair share of political instability and experimentation about how we should govern ourselves”, noting: “There might be new names being ascribed to some of the supposed new ideas being canvassed by some today, but I daresay, on close examination, we would discover they are not new: we have tried them here, and they have failed.” He then urged Africa to be wary of ‘saviours’ in military fatigues. “We know about all-powerful, cannot-be-questioned Messiahs; we know about liberators, and we know about redeemers and deities in military uniform. It might sound new to some, but those of us who have been around for a while have heard the argument made passionately that democracy was not a suitable form of government if we wanted rapid development.”

In Mr Akufo-Addo’s opinion, “It is a tired argument that was regularly used by coup apologists. It is also not new to have political parties and politics, in general, being denigrated, indeed, there used to be national campaigns of fear waged against politics and political parties”. “It took time and it took long battles, but, in the end, a consensus did emerge, and we opted for a multi-party democratic form of government under the Constitution, which ushered in the Fourth Republic”, the president pointed out. Using his country as an example, Mr Akufo-Addo said although the 1992 Constitution “is not a perfect document, Constitutions do not ever pretend to be; but it has served us well these past thirty-two (32) years, considering where we have come from”. “It is a sacred document that should not be tampered with lightly, but, I hasten to add, our Constitution did not descend from heaven, we, Ghanaians, drew it up to serve our needs, and we can amend it to suit our changing needs and circumstances”. In his view, “We should work toward finding a consensus on the changes that the majority of Ghanaians want [to be] made to the Constitution. Mr Speaker, democracies are founded on elections, and the holding of free and credible elections ensures that people have confidence in the government that emerges at the end of the process”.

A sixth peaceful transition will cement Ghana’s reputation as a democracy icon in the turbulent sub-region.

In East Africa, South Sudan, the continent’s youngest country, has seen its leader, President Salva Kiir, postpone elections several times – a strategy that has helped him to hold on to power since 2005, after he took over from the country’s independence leader, John Garang, who died that year. Since South Sudan’s independence in 2011, the 72-year-old former guerilla army commander was authorised to lead the country for a four-year term but has held on up to now. He has postponed elections in 2015, 2018, 2020, and 2022. He appears to be exploiting a 2011 Transitional Constitution that does not include a limit on presidential terms. A 2020 National Dialogue unanimously called for one to be adopted. Should Kiir stick to his promise and allow elections to be held in South Sudan, Africa would have gained one more democracy convert, which would serve the country and the continent well. However, if Kiir persists in his tricks, the ‘Iron Man’ image of the young independent country would prevail.

In North Africa, Although Algeria is among the countries that adopted multiparty democracy early on in that part of the continent, it has shown little regard for democracy. The military, after the country’s 1991 democratic elections, stopped the Islamic Salvation Front from taking office. This sparked a civil war that wasted an estimated 200,000 lives. Long-time ruler Abdelaziz Bouteflika rode on that to take power in 1999. President Abdelmadjid Tebboune, the former prime minister under Bouteflika, is currently at the helm of affairs of the ruling National Liberation Front (FLN). The government has come under heavy criticism and pressure from citizens who are demanding more freedoms and participation in the tightly-controlled electoral processes. Algeria has seen several protests and demonstration for media freedom, freedom of speech and transparency in the conduct of elections. A free and fair presidential election in December could set a new democratic roadmap for Algeria.

Fellow North African country Tunisia, is currently being ruled by an autocrat, President Kaïs Saïed, who has targeted and dissolved all democratic institutions of the country that serve as checks and balances. The auto-coupist, who won power in 2019 through a democratic process, dissolved the country’s opposition-controlled parliament in 2021. He saw the legislature as a hurdle. Following the ousting of the country’s dictatorial ruler, Zine el Abidine Ben Ali in 2011, “Tunisia’s 2014 Constitution created a semi-presidential system whereby the parliament elects the prime minister, who then selects ministers and leads the government. The president serves as head of state. This arrangement was a direct response to the executive overreach and impunity that typified Ben Ali’s 24-year rule”, the Africa Centre for Strategic Studies says. President Saïed also dismissed Prime Minister Hichem Mechichi, and appointed one of his own, Najla Bouden, who is answerable to him, without parliamentary approval and now rules by decree. He also suspended the country’s Constitution in 2021 and wrote one of his own in 2022 that makes him the head of state and government. Additionally, he dissolved the Supreme Judicial Council in February 2022 and replaced it with an appointed body. Per his new Constitution, he can unilaterally dismiss and appoint magistrates. Already, the president has barred international observers from monitoring the upcoming elections.

He cracks down on dissent, restricts media and civil society freedoms, and persecutes political opponents. In such a political environment, it is easily predictable that the outcome of this year’s elections in Tunisia will be nothing but the will and orchestration of President Saïed. For now, democracy is dead in Tunisia and it would only take a revolution to reset the country to democratic settings.

In Central Africa, Rwanda, which has been governed by Paul Kagame for the past 24 years, will also be heading to the polls this year. In a 2015 constitutional referendum, Rwandans voted overwhelmingly to allow President Paul Kagame to stand again for office beyond the end of his second mandate, which ended in 2017. Kagame won the 2017 elections, with nearly 99% of the vote. His current term ends this year, 2024, but he is eligible to run for two more terms, thus, possibly and likely going to be in power until 2034, something his adviser sees nothing wrong with. “Here in Rwanda, a possible extension of our President’s term of office is currently not an issue,” Jean-Paul Kimonyo told DW, noting: “We want more prosperity and we need strong leadership for this. And Rwandans are currently very satisfied with their leadership.”

Human Rights Watch, in 2022, said Kagame’s administration continued “to wage a campaign against real and perceived opponents of the government”. It said the administration cracked down on political opposition and restricted the people’s right to freedom of expression, association, and peaceful assembly. Critics were arbitrarily arrested and some even said they were tortured in state custody. There were many forced disappearances and suspicious deaths that were not investigated by the authorities.

However, Kagame, who has been re-elected as a candidate for his party, says Rwanda can’t be like the others. “As Rwandans, we cannot do things as everybody else in the usual way. The challenges they face and those that we confront are different. The one thing that you can do, and everyone starts saying, ‘Rwanda did this, Rwanda did that!’ Others would do things a hundred times worse, but no one will ever talk about them. For us to live well, we need to do things in a unique way so that even those who want to accuse us of all evils can hardly find any wrongs about us,” said President Kagame in his acceptance speech after being re-elected as chairman of the RPF-Inkotanyi.

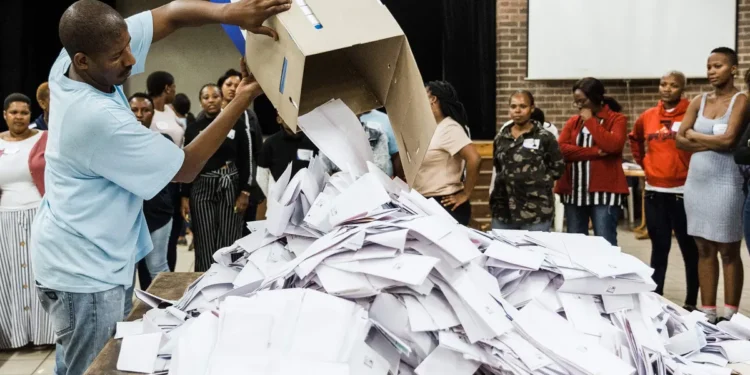

Further south to the continent, Mozambique’s October elections will be a straight fight between the ruling Frente de Libertação de Moçambique (FRELIMO) party and the opposition Resistência Nacional Moçambicana (RENAMO) party. A third force, Movimento Democrático de Moçambique (MDM), is also in the mix of things. The FRELIMO government has ruled in a dictatorial style and corrupted every democratic institution. It essentially makes Mozambique a one-party state despite the existence of other parties. In the 2019 election, for example, there were widespread reports of ballot box stuffing. Observers described it as the least transparent election since the country set onto its multiparty journey in 1994 after a 15-year civil war fought between FRELIMO and RENAMO that destroyed an estimated one million lives. In the 2019 poll, the National Election Commission declared President Filipe Nyusi the winner with 73 per cent of the vote. In 2019, FRELIMO increased its majority in the 250-seat Assembly from 144 seats to 184 seats. Also, FRELIMO elected all 10 of the provincial governors. RENAMO gained 45 and 47 per cent of parliamentary seats in the 1994 and 1999 elections, respectively, before seeing a drop to 20 per cent by 2009. RENAMO accused FRELIMO of manipulating election results, which set off a low-intensity conflict between 2011 and 2016, only coming to an end after another peace deal in 2019. Such a political environment of distrust often does not bode well for democracy. In such situations, the incumbent always uses state authority and machinery to have its way through fair or foul means. From the above, it appears the juntas and dictators in some African countries are not ready to cede their authority to anyone. They are bent on manipulating constitutions, restricting electoral and media freedoms, and using the machinery of the state to perpetuate themselves in power. It may take a political earthquake to restore those countries to the path of democracy. Meanwhile, those who are already making progress on that path need encouragement to ward off the temptation to stray off course.